Open Data Impact:

When Demand and Supply Meet

Key Findings of the Open Data Impact Case Studies

By Stefaan Verhulst and Andrew Young1

Recommendation #1: Focus on and define key problem areas where open data can add value.

-

A core premise offered by our case studies is that the impact of open data is often dependent on how well the problem it seeks to address is defined and understood. It is therefore essential for open data advocates and practitioners to clearly define their goals, the problem they are seeking to address, and the steps they plan to take. Some possibilities for how this focus can be achieved:

- Set up a crowdsourced “Problem Inventory” to which users can contribute specific questions and answers, both of which can help define open data projects. The UK Ordnance Survey’s GeoVation Hub is an interesting model focusing on the latter. It poses very specific questions (e.g., How can we improve transport? How can we feed Britain?) for users to answer using OS OpenData.

- Facilitate user-led design exercises to help define important public and social problems and how open data can help solve them.

- To guide such exercises, it may be useful to establish Problem and Data Definition toolkits – potentially modeled on and informed by Freedom of Information requests – that help formulate clearly defined public issues and connect them with potentially useful open data streams.

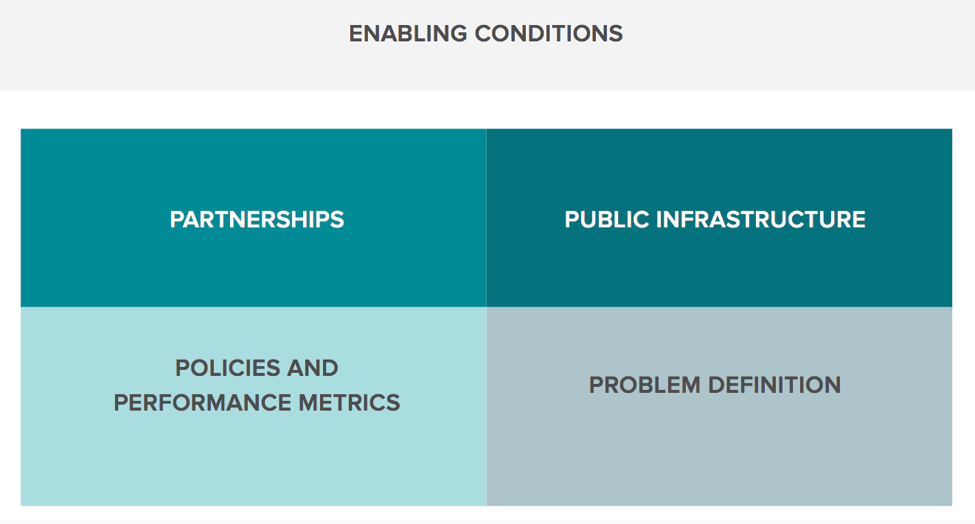

Recommendation #2: Encourage collaborations across sectors (especially between government, private sector and civil society) to better match the supply and demand of open data.

-

Large public problems are by definition cross-sectoral and inter-disciplinary. They define boundaries and require a variety of expertise, knowledge and data in order to be successfully addressed. It therefore stands to reason that the most successful open data projects will similarly be collaborative and work across sectors and disciplines. Working in a collaborative manner can help draw on a diverse pool of talent, and can also lead to innovative, out-of-the-box solutions. Perhaps most importantly, by allowing data users and data suppliers to work together and interact, collaborative approaches can improve the match between data demand and supply, thus enhancing the overall efficiency of the demand-use-impact value chain for open data.

Some pathways to achieving the required collaborative and cross-sectoral approaches:

- Create data collaboratives to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the demand-use-impact cycle. The value of data collaboratives is clearly illustrated by New Zealand’s Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority’s data sharing with construction companies, which is projected to deliver NZ$40 million in savings. In addition, NOAA’s Big Data Partnership, which formalized a sector partnership with five leading private-sector data and cloud technology companies, is also a good example.

- Engage and nurture data intermediaries, especially from civil society, to help spread awareness and disseminate data (and their findings) more widely. Data intermediaries play a particularly important role in countries with low technical capacity (e.g., as evident in our Tanzanian case study); they offer a vital link between technology and society, helping citizens maximize and make real, effective use of data in their everyday lives.

Recommendation #3: Approach and treat data as a form of vital 21st century public infrastructure.

-

Too often, policy- and decision-makers focus solely on opening up data, as if open data on its own provides a silver bullet for a society’s problems. In fact, as repeatedly evidenced in our case studies, data – in its raw form – needs to be supplemented by a host of other commitments: sustained and sustainable funding, skills training among those charged with data collection and use, and effective governance structures for every step of the data collection and use cycle. Approaching data in this broader, more holistic way means treating it as a vital form of public infrastructure, one at the heart of a society or nation, essential for its success, and embedded within wider social, economic and political structures.

There are several steps policymakers can take to advance a “data-as-infrastructure” approach. These include:

- Developing a systems design and mapping methodology. Mapping the public and private sector data infrastructure, as well as local, national and global data infrastructures that may impact the value creation of open data is a first and necessary step to approach data as infrastructure. A systems map could enable the more targeted, coordinated, collaborative development of open data technical standards and best practices across sectors.

- Embracing and implementing the Open Data Charter,4 which seeks to “foster greater coherence and collaboration” around open data standards, practices and, in particular, the following principles:

- Open by default

- Timely and comprehensive

- Accessible and usable

- Comparable and interoperable

- For improved governance and citizen engagement

- For inclusive development and innovation

- Leveraging existing public infrastructure, such as libraries, schools and other cultural and education institutions, so that data is more firmly embedded into other forms of public investment and public life. Open Referral, for example, is creating a data backend for the social safety net, allowing pilot partners, including libraries, to tap into a wide, interconnected range of potentially impactful data on civic and social services.

- Developing skills and capacity around data collection, cleaning and standardization to ensure better quality data is being released. This is especially important within agencies and organizations releasing data (to ensure the quality of data), but also, to the extent possible, within the community of users.

- Viewing and treating open data as a public good, something to which citizens and taxpayers are entitled. Moving toward a view of open data as a public good requires as much of a cultural change as a policy change: As our case studies have repeatedly shown, the success of open data initiatives depends crucially on government stakeholders accepting that citizens – whether researchers, journalists or just average individuals – have a right to demand access to government data.

Recommendation #4: Create clear open data policies that are measurable and allow for agile evolution.

-

Our research illustrates the vital enabling role played by a national legal and regulatory framework that supports open data. Well-articulated internal rules and priorities are equally important when the releasing entity is a company or other organization. In both cases, clarity is essential: Open data thrives when there is an unambiguous commitment to its cause. Importantly, open data policies should include provisions to measure the success (or otherwise) of an initiative; systems for measurement and assessment are vital to ensuring accountability.

There are several steps policymakers can take to ensure the necessary clarity of open data policies. These include:

- Co-creating open data policies with citizen and other groups, which can be an important way not only of drafting inclusive (and thus more legitimate) policies, but also of ensuring that policies are responsive to actual conditions and needs. Our research repeatedly shows that policies drafted without adequate public input and participation are less effective than those that draw on a wider range of experiences and expertise. Of course, attention must be paid to knowledge and power asymmetries involved in such co-creation processes.

- Engaging the public in defining and monitoring metrics of success: Citizen participation in measuring the results of open data initiatives is as important as in drafting policies, and for the same reasons. It is a vital part of ensuring accountability and in enhancing the legitimacy and effectiveness of open data projects.

- Creating a “Metrics Bank” of important indicators, with input from stakeholders, researchers and experts in the field. Such a Metrics Bank could be built around the variety of categories of open data’s impacts, such as economic concerns (like return on investment or private sector economic revenues generated), public problem solutions (lives saved, increases in the efficiency of service delivery), and others. In line with the previous suggestion, the Metrics Bank should be reviewed on a regular basis by a citizens’ group or panel created specifically for that purpose.

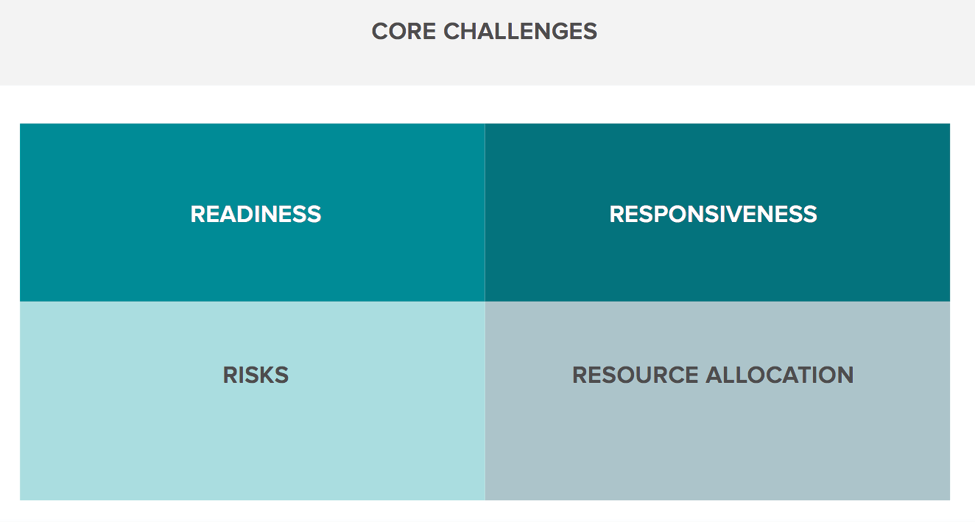

Recommendation #5: Take steps to increase the capacity of public and private actors to make meaningful use of open data.

-

Repeatedly, we have seen how open data initiatives are limited by a lack of capacity and preparedness among those who could potentially benefit most. Often, this manifests quite simply as a lack of awareness: Those who do not know about the potential of open data are likely to use and benefit less from it. It is important to recognize that low capacity is a problem both on the demand side and supply side of the open data value chain – policymakers and those tasked with releasing data are often as unprepared as intended beneficiaries.

Several steps can be taken to increase capacity and preparedness:

- Set up coaching and training centers to teach policymakers and key stakeholders among citizens about the potential benefits and applications of open data. Brazil’s Open Budget Transparency Portal, for instance, benefited tremendously from TV campaigns and regular workshops designed to train citizens, reporters and public officials on how to use the Open Budget Transparency Portal. In addition, a combined overview or searchable directory of coaching opportunities already in place and provided by, for instance, the GovLab Academy and the Open Data Institute, could enable easier navigation and matching of interests and needs worldwide.

- Establish mentor and expert networks for those seeking to use open data. Such networks can serve as valuable resources, providing guidance on the optimal uses of open data and helping citizens and policymakers overcome hurdles or navigate obstacles.

- Invest in and promote user-friendly data tools, such as data visualizations and other analytic tools. While raw data can often be overwhelming for novice users, platforms and apps that include analytics and visualizations are often far more accessible. Notable examples from our case studies include the UK Ordnance Survey’s OS OpenMap, NYC’s Business Atlas and Mexico’s Mejora Tu Escuela.

- Use online and offline meet-ups and similar tools to create a culture that encourages knowledge sharing and collaboration. Many off-the-shelf tools already exist; if integrated within open data initiatives or data labs – like the Justice Data Lab in the United Kingdom – they can provide a helpful online supplement to the types of training efforts and expert-mentor networks mentioned above.

Recommendation #6: Identify and manage risks associated with the release and use of open data.

-

As our case studies have shown, open data can be a force for good, but it is not without risks. Two of the most important risks involve potential violations of privacy and security that can result from widespread releases of data. Such risks were apparent in a number of our case studies, notably Eightmaps, Brazil’s Open Budget Transparency Portal, and New York’s Business Atlas. Mitigating such risks is essential not only for its inherent value, but also because privacy and security violations undermine trust in open data and, over the long run, limit its potential.

Several steps can be taken to mitigate risks:

- Develop data governance “decision trees” to help decision-makers track the potential risks and opportunities around certain types of data releases. These decision trees can also help weigh the pros and cons and relative risks of data releases.

- Create innovative, collaborative open data risk management frameworks so that governments and other institutions releasing data can draw on a clear, structured, step-by-step process to strategically respond to breaches of privacy, security or other risks. NOAA, for example, is working with outside experts to crowdsource new frameworks for data management.

- Involve all stakeholders (including citizen groups) in developing data quality and risk standards. A participatory, collaborative approach to mitigating risks can build trust and help achieve the right balance between social goods like innovation, on the one hand, and risks like privacy and security, on the other hand. Crowdsourcing can be a valuable tool here, allowing policymakers to solicit a wide range of responses from diverse stakeholder groups.

Recommendation #7: Be responsive to the needs, demands and questions generated from the use of open data.

-

We have seen that public participation is essential in the drafting of open data policies and in decisions about what data to release. It is equally important in understanding the impact of open data and in taking advantage of the opportunities it offers. For example, open data can generate insights that require government action; open data can likewise reveal inefficiencies that need concrete steps in order to be addressed. And as we have seen in the Brazilian case study on preventing government corruption, meaningful responsiveness requires the ability to take such steps and actions; what’s required are communities focused on problem solving, not simply on releasing data.

Meaningful responsiveness can be achieved through the following methods:

- Develop open and online feedback mechanisms, including Q&As, ratings and feedback tools to gauge public opinion and solicit insights from citizens. For example, Denmark’s Open Address Initiative has a single portal for users to correct data errors across all agencies. Simplified mechanisms such as this help establish a virtuous open data cycle, allowing open data to generate insights and ensuring meaningful action on those insights.

- Designate an open data ombudsman function to consistently track the usefulness of open data and whether necessary follow-up actions are being taken. This ombudsman should itself be open and transparent, and ideally include a wide range of stakeholder inputs.

Recommendation #8: Allocate and identify adequate resources to sustain and expand the necessary open data infrastructure in a participatory manner.

-

As noted, open data initiatives are often cheap to get off the ground, but require resources and investment over time. Goals such as increased participation and transparency are laudable, but

without resource commitments, they may remain unachievable. Kenya’s Open Duka project is a good example of a laudable open data initiative that has been limited by a lack of resources. Similarly, Canada’s Open Charity Initiative T3010 has not yet been updated since its original 2013 release, in part due to a lack of funding, with the result that anyone seeking recent data on Canadian charities must now scrape information independently.

Adequate resource allocations can be achieved by:

- Participatory budgeting initiatives, which allow citizens to choose their priorities and how public funds are allocated. Such initiatives can ensure that the most useful open data initiatives receive the most funding.

- Undertaking more rigorous cost/benefit analyses of open data initiatives, which would allow policymakers and other stakeholders to assess the relative opportunities offered by projects against their costs and possible risks. Among our case studies, NOAA and the UK Ordnance Survey both commissioned cost/benefit studies before launching their projects – this played a vital role in bolstering support and long-term commitments from policymakers and government stakeholders.

- Exploring innovative avenues for funding, especially crowdsourcing, which may offer the public (and other interested parties) an avenue not only for funding initiatives but also for establishing and ensuring the sustainability of their priorities.

Recommendation #9: Develop a common research agenda to move toward evidence-based open data policies and practices.

-

The most effective avenue to understanding how open data works, and how to achieve maximum positive impact, is through collaboration. Our knowledge of open data today is in many ways fragmentary, spread across organizations and individuals who are themselves scattered across the globe. There is a need for more communication and pooling of analysis (and resources). To achieve the potential of open data, we need a common research agenda, based on a wider evidential foundation. Importantly, this research framework should integrate a better understanding of impact into its core agenda: Too often, open data research focuses simply on the best ways of releasing data, with impact – positive or negative – being simply an afterthought.

To achieve this common research agenda, we should:

- Set up mechanisms for communication and interaction among various stakeholders (individuals and organizations) currently working in the field of open data. Such mechanisms could include annual meetings or conferences, listservs, monthly hangouts, and other offline and online tools. The goal of these interactions would be to trade insights and ideas, to share evidence, and to collaboratively develop best practices. Events like the Open Data Research Summit within the context of the International Open Data Conference, may provide, for instance, the impetus toward improved exchange and collaboration among researchers in this field.

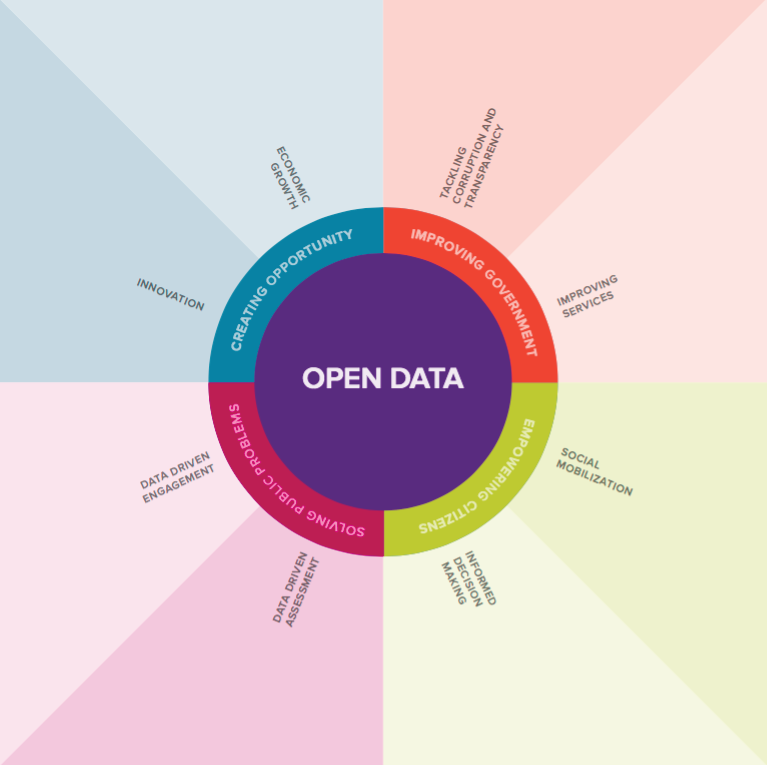

- Build on the taxonomy of impact developed through these 19 case studies and have other researchers test the premises we identified above. In addition, the Open Data research community could consider further fine-tuning of the open data common assessment framework5 GovLab developed together with Web Foundation and others in order to create a standardized tool for evaluating every stage of the open data value chain.

- Create a directory (perhaps in wiki format) of various assessment frameworks (in addition to our own), spread across countries and sectors. Such a directory would also include a list of key contacts and organizations, and would help facilitate discussion by establishing a baseline of sorts toward achieving a common research agenda.

Recommendation #10: Keep innovating.

-

Open data fuels innovation, but how can we innovate open data? We need to recognize different forms and models of open data – including big and small data, text-based data – and encourage stakeholders to think broadly about what data is and what open really means. Even while we work to better understand open data and its impact (for example, through exercises such as this one), we should foster a culture of proactive experimentation and innovation.

There are many ways to foster such a culture:

- Institutionally, we can look at creating new entities or intermediaries, for example a global open data innovation lab whose explicit purpose would be to think outside the box and research new models of open data that can be tested across sectors, regions and use cases.

- The need for collaborative research mentioned above can also be institutionally developed into a cross-border and interdisciplinary open data innovation network. Such a network would draw on global expertise and ideas.

- Perhaps most importantly, we need to be open to new ideas and insights, and always remain in question mode. This report has outlined several recommendations and suggestions for how to maximize the value of open data. But we recognize that this is just a beginning. Our research has raised as many questions as it has suggested answers.