OPEN DATA IN DEVELOPING ECONOMIES

Toward Building an Evidence Base on What Works and How

By Stefaan Verhulst and Andrew Young

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- I. What makes open data uniquely relevant to developing economies?

- II. How can the impact of open data on developing economies be captured and evidence be developed?

- III. The Realized and Intended Impacts of Open Data in Developing Economies across Sectors

- IV. How can open data be leveraged as a new asset for development?

Executive Summary

Across the world, governments are acting on the belief that systematically making data more accessible can provide an important new asset to usher in positive social and economic transformation. This trend is not limited to countries with more developed economies. Although the bulk of data in terms of quantity has thus far been released in developed countries, a growing number of developing economies — in Asia, in Africa, in Latin America — have also been adopting open data plans and policies, and publishing government datasets that previously remained locked away in closed databases. This move toward open data is part of a broader global trend toward more data-driven decision making in policymaking and development — a manifestation of what is sometimes called the “data revolution.”

The growing enthusiasm surrounding open data gives rise to several questions about open data’s unique features to foster change. Can it truly improve people’s lives in the developing world — and, if so, how and under what conditions?

The goal of this paper is to map and assess the current universe of theory and practice related to open data for developing economies, and to suggest a theory of change that can be used for both further practice and analysis. We reviewed the existing literature, consulted with the open data community and sought to collect evidence through a series of 12 in-depth case studies spanning multiple sectors and regions of the world. In particular, we sought to answer the following three questions:

- What makes open data uniquely relevant to developing economies?

- How can the impact of open data in developing economies be captured and evidence be developed?

- How can open data be leveraged as a new asset for development?

What makes open data uniquely relevant to developing economies?

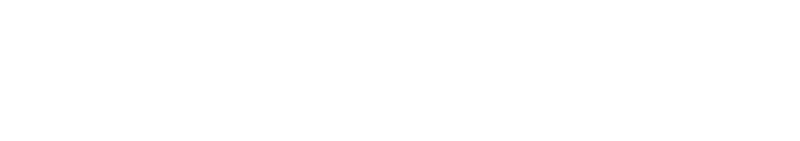

Although there has been much focus on the potential of data to usher in change, what makes open data different is often not as well recognized, with supporting analysis often speculative or anecdotal. Understanding the distinguishing features of open data is important to subsequently document how open data works — its mechanisms and pathways — and in doing so, to build a more solid evidence foundation for open data in development. Based on our review of the existing narratives and theories in the literature, we identified six unique features that are believed to make open data specifically relevant — or potentially powerful — in the context of developing countries. They reflect some of the features that are often also associated with the value of open source or open innovation in a developing context; and explain why open data is closely connected with the twin trends of open government and open development.

Participation

By facilitating citizen participation and mobilization, open data can allow a wider range of expertise and knowledge to address and potentially solve complex problems.

Scrutiny

Because open data is subject to greater scrutiny and exposure than inaccessible institutional data, there is potential for enhanced review and improvement in the quality of government data by actors outside government.

Trust

Because open data increases transparency and avenues for citizen oversight, unlocking data can lead to higher levels of trust throughout societies and countries.

Value Amplifier

Finally, opening government datasets in a flexible and equal manner can amplify the value of data by filling — and identifying — important data gaps in society.

Equality

Open data can lead to more equitable and democratic distribution of information and knowledge — though, several observers have also pointed out that just releasing open data can play a role in further entrenching power asymmetries related to access to technology and data literacy.

Flexibility

Because open data is subject to greater scrutiny and exposure than inaccessible institutional data, there is potential for enhanced review and improvement in the quality of government data by actors outside government.

How can the impact of open data in developing economies be captured and evidence be developed?

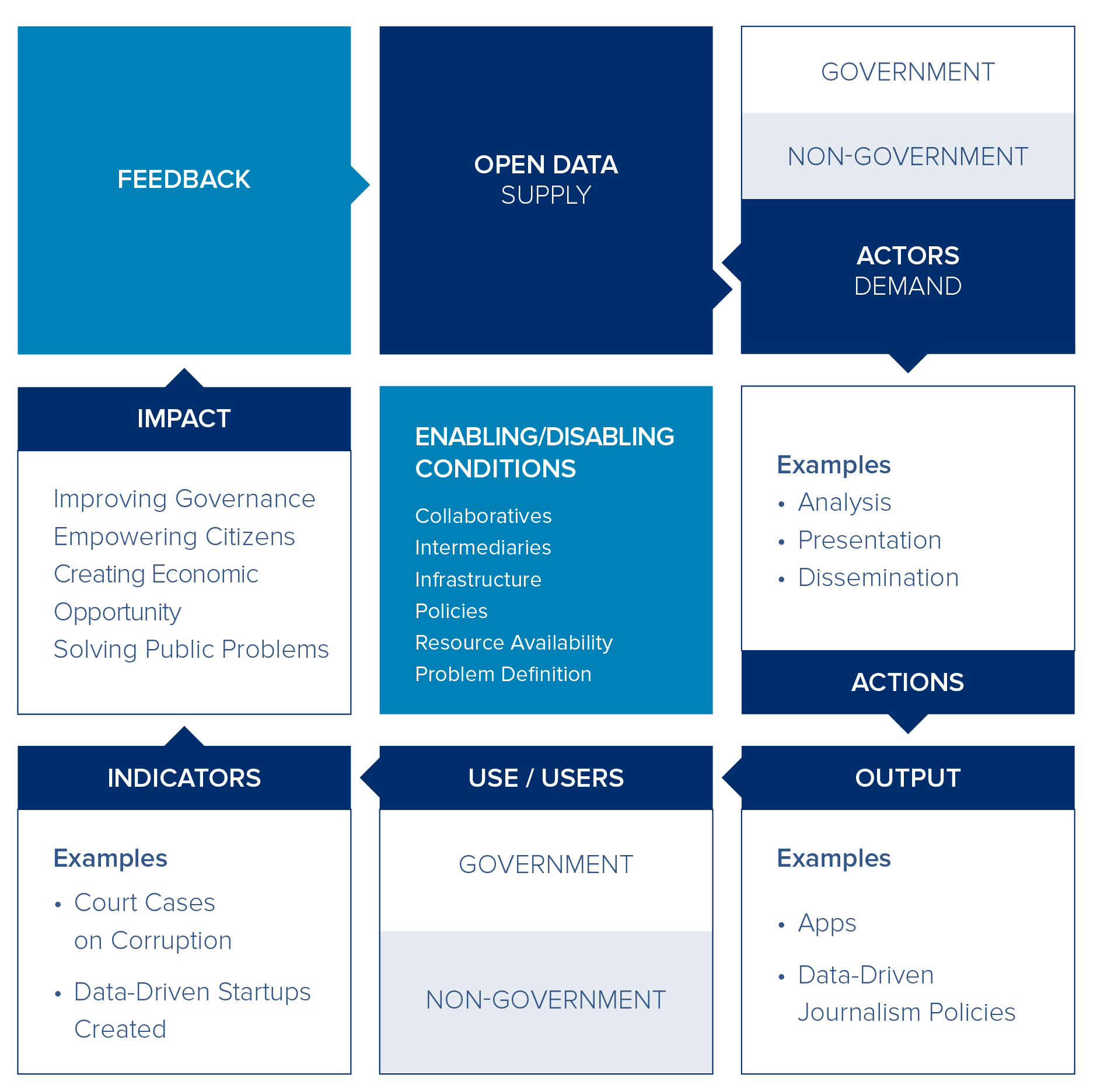

To analyze and capture existing evidence and to inform future comparative analyses across sectors and countries, we developed, expanded, and sought to start testing the following Change Theory and/or Logic Model:

Open data (supply), when analyzed and leveraged by both governmental and non-governmental actors (demand), can be used in a variety of ways (actions and outputs), within the parameters established by certain enabling conditions (and disabling factors), to improve government, empower citizens and users, create economic opportunity, and/or solve societal problems (impact).

This logic model is built around the premise (informed by the case studies) that high-impact open data projects are the result of matching supply and demand so that open data can be effectively used to inform specific activities and outputs aimed at improving development. These outputs and activities can, in turn, serve a broader and more diverse group of users and objectives.

We categorized open data’s (intended or realized) impact on development along the following pathways:

- Creating economic opportunity, by enabling business creation, job creation, new forms of innovation, and more generally spurring economic growth

- Helping to solve complex public problems by improving situational awareness, bringing a wider range of expertise and knowledge to bear on public problems, and by allowing policymakers, civil society, and citizens to better target interventions and track impact

- Improving governance, for instance by introducing new efficiencies into service delivery, and increasing information sharing within government departments

- Empowering citizens by improving their capacity to make decisions and widen their choices, and by acting as a catalyst for social mobilization

We found that there is wide variability documented evidence. Much of the literature remains focused on the potential of open data to bring about positive benefits — absent real evidence and data. Little distinction is made between intent, implication, and impact, blurring our understanding of what the true value may be of open data. Several of the cases we analyzed did provide evidence that open data had an impact on people’s lives while some failed to achieve notable, scalable impact, or worse, created new harms or risks.

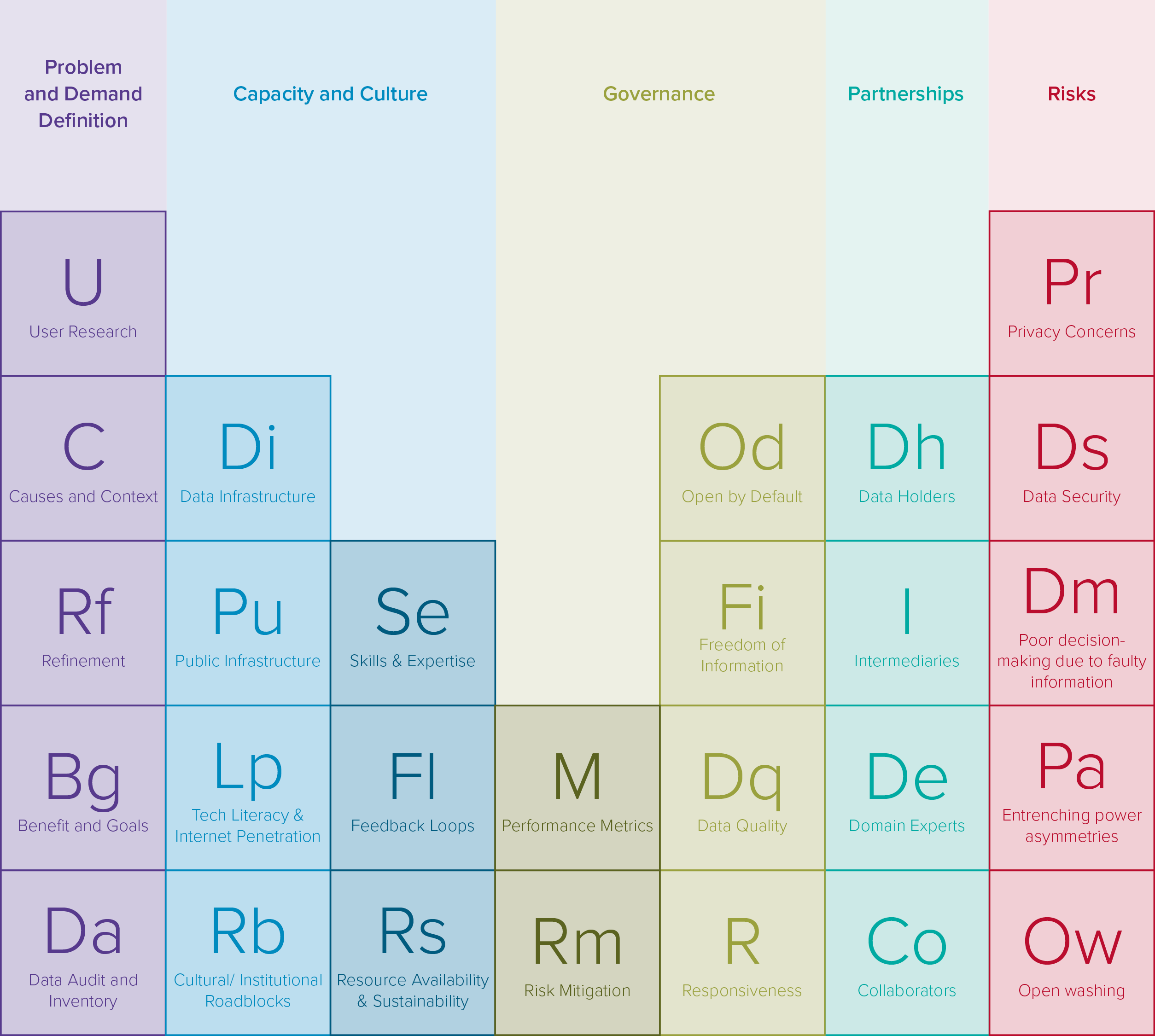

To address the variability in evidence, and start focusing on testable premises of how, and under what conditions, open data works best in developing economies, we subsequently identified 27 enabling or disabling factors within the following five categories:

- Problem and Demand Definition: whether and how the problem to be addressed and/or the demand for open data are clearly defined and understood

- Capacity and Culture: whether and how resources, human capital, and technological capabilities are sufficiently available and leveraged meaningfully

- Partnerships: whether collaboration within and, especially, across sectors using open data exist

- Risks: whether and how the risks associated with open data are assessed and mitigated

- Governance: whether and how decisions that affect the use of open data are made in a responsive manner

By combining these factors we developed a “Periodic Table of Open Data’s Impact Factors” that can be used (and further fine-tuned) as a canvas or checklist toward designing open data initiatives. Together with the logic model, the periodic table can also be used as a framework for analyzing and capturing key evidence of what contributes to “successful” open data efforts in developing economies.

Periodic Table of Open Data Elements. View interactive periodic table here.

How can open data be leveraged as a new asset for development?

Despite the variability in evidence, we identified several key take-aways enabling us to make the following specific recommendations for open data practitioners and decision makers, including donors like USAID, on how to better leverage open data as a new asset for development.

- Focus on and define the problem, understand the user, and be aware of local conditions. The most successful open data projects are those that are designed and implemented with keen attention to the nuances of local conditions; have a clear sense of the problem to be solved; and understand the needs of the users and intended beneficiaries. Projects with an overly broad, ill-defined or “fuzzy” problem focus, or those that have not examined the likely users, are less likely to generate the meaningful real-world impacts, regardless of funds available. Too often, open data projects have less impact because they are overly data-focused rather than problem- and user-focused.

- Focus on readiness, responsiveness, and change management. Implementing open data projects often requires a level of readiness among all stakeholders, as well as a cultural transformation, in the way governments and institutions collect, share, and consume information. For development funders, however, this important determinant of success can imply difficult decisions regarding high-potential open data initiatives in developing economies that lack clear institutional readiness or demonstrated responsiveness to feedback.

- Nurture an open data ecosystem through collaboration and partnerships. Data does not exist in isolation. The success of open data projects relies on collaboration among various stakeholders, as well as collaboration with data scientists and topic or sector experts. During the problem definition and initial design phase, practitioners and funders should explore the types of collaborations that could increase uptake and impact. Such partnerships could, for example, take place with other data providers (perhaps from different sectors), like-minded international or local organizations, and established intermediaries such as journalists or industry groups.

- Have a risk mitigation strategy. Open data projects need to be mindful of some of the important risks associated with even the most successful projects. Notably, these risks include threats to individual privacy (for example, through insufficiently anonymized data or commingling multiple datasets to create new privacy issues), and data security. Funders should ensure that projects that deal in information that is potentially personally identifiable (including anonymized data) have audited any data risks and developed a clear strategy for mitigating those risks before proceeding with the project.

- Secure resources and focus on sustainability. Open data projects can often be initiated with minimal resources, but require funding and additional sources of support to sustain themselves and scale up. It is important to recognize that access to funding at the outset is not necessarily a sign that open data projects are destined for success. A longer term, flexible, business model or strategy is a key driver of sustainability, and should be developed in the early stages of the design process.

- Build a strong evidence base and support more research. As demonstrated in this paper, of perhaps even greater importance is the development of an evidence base that can provide feedback and indications of what works and what doesn’t work, to maximize the impact of the (often scarce) resources available. The analytical framework provided in this report could act as a starting point for developing more systematic and comparative research that would allow for more evidence-based open data practice. In addition, to turn insights gathered into more evidence-based practice we need to translate these findings into new methodologies or checklists of key steps and variables (leveraging the Periodic Table provided in this paper).

In conclusion, given the nascent nature of existing open data initiatives, the signals of open data’s impact in developing economies are still largely muted, as evidenced in the examples discussed in our paper. Our goal in this paper was not to use these examples as the ultimate proof of open data’s importance for development; rather, we have picked up these signals and placed them into an analytical framework to enable further practice and analysis going forward. It is only with this type of structured analysis that we can gain a systematic and comparative evidence base of if and how open data is having meaningful impact on conditions on the ground in developing economies.

In this table, we list the case studies developed to inform this paper, identify the intended impact of each, and note which of the key take-aways described above are represented in the projects studied.

| Case Study | Summary | Intended Impact | Clear Problem Definition |

Readiness, Responsiveness and Change Management |

Open Data Ecosystem and Partnerships |

Risk Mitigation Strategy |

Resources and Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burundi: Open Results- and Performance-Based Financing | Results-based financing (RBF) in Burundi is an instrument that links development financing with pre-determined results, aimed to strengthen accountability and transparency in government expenditure. | Improving Government | | | | | |

| Cambodia: Opening Information on Development Efforts | Open Development Cambodia helps to improve the public’s awareness of current and historical information on development efforts through a data-drive online platform. | Improving Government | | | | ||

| Colombia: Establishing Climate Resilience in Agriculture | The Aclímate Colombia project processes, analyzes, and publishes open government datasets to help farmers access climate and market data to improve their decision making and livelihoods. | Creating Opportunity | | | | ||

| Ghana: Empowering Smallholder Farmers | Esoko is a for-profit communication tool that provides farmers repackaged data from different sources (including government and crowd-sourced data) via mobile phones to empower smallholder farmers. | Creating Opportunity | | | | | |

| India: Open Energy Data | The Electricity Supply Monitoring Initiative (ESMI) collects real-time power quality information in an effort to monitor power quality in urban and rural India. | Improving Government | | | | | |

| Jamaica: Open Data to Benefit Tourism | Jamaica uses open data to increase and improve its tourism sector, particularly by combining crowdsourced mapping data with open government data to create more participatory tourist maps. | Creating Opportunity | | | | ||

| Kenya: Improving Voter Turnout with Open Data | In the lead up to Kenya’s 2013 general election, Code 4 Kenya published election data on the website GotToVote!, which provided citizens with voter registration center information, and easy-to-access information about registration procedures. | Empowering Citizens | | | | | |

| Nepal: Open Data to Improve Disaster Relief | A number of crowdsourced and open mapping data platforms helped humanitarian relief efforts in the wake of Nepal’s 2015 earthquake. | Solving Public Problems | | | | | |

| Paraguay: Predicting Dengue Outbreaks with Open Data | The National Health Surveillance Department of Paraguay opened data related to dengue morbidity, which was used to create an early warning system. | Solving Public Problems | | | |||

| South Africa: Code4SA Cheaper Medicines for Consumers | Code for South Africa uses data from the National Department of Health for its Medicine Price Registry Application (MPRApp), an online tool that helps patients identify and access cheap medicine. | Empowering Citizens | | | | ||

| Tanzania: Open Education Dashboards | Two portals in Tanzania publish education data in efforts to improve Tanzania’s schools. The first, the Education Open Data Dashboard (educationdashboard.org), supports open data publication, accessibility and use. The second, Shule (shule.info), attempts to use open data to catalyze social change in Tanzania. | Empowering Citizens | | | |||

| Uganda: Opening Health Data to Improve Outcomes | Uganda’s iParticipate project uses open data available from government portals and other sources to analyze health service delivery and public investments in health projects. | Improving Government | | | | |

LIST OF ACRONYMS |

|

| BBW | Banana Bacterial Wilt |

| BODI | Burkina Open Data Initiative |

| CIAT | International Center for Tropical Agriculture |

| DFID | Department for International Development, United Kingdom |

| EITI | Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative |

| ELOG | Elections Observation Group |

| EOSDIS | Earth Observing System Data and Information System |

| ESM | Electricity Supply Monitor |

| ESMI | Electricity Supply Monitoring Initiative |

| EITI | Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative |

| GODAN | Global Open Data Initiative for Agriculture and Nutrition |

| IDRC | International Development Research Centre |

| IEBC | Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission, Kenya |

| IMCO | Mexican Institute for Competitiveness |

| MERC | Maharashtra Electricity Regulatory Commission |

| MPR | Medicine Price Registry, South Africa |

| MPRApp | Medicine Price Registry Application |

| NERC | National Ebola Response Centre |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| OD4D | Open Data for Development |

| ODC | Open Development Cambodia |

| ODI | Open Data Institute |

| OGP | Open Government Partnership |

| OSM | Open Street Map |

| PEG | Prayas Energy Group |

| PHC | Primary Health Care Centre |

| PII | Personal Identifiable Information |

| RBF | Results Based Financing |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TAP | Transparency, Accountability and informed Participation |

| UNICEF | The United Nations Children's Fund |

| USAID | United States Agency for International Development |

| WOUGNET | Women of Uganda Network |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our partners at USAID: Mark Cardwell, Samir Doshi, Priya Jaisinghani, Merrick Schaefer, Vivian Ranson, Josh Machleder, Brandon Pustejovsky, Subhashini Chandrasekharan; and at FHI 360: Hannah Skelly and Abdul Bari Farahi who provided essential guidance and input throughout the project.

We would also like to acknowledge the great team responsible for the case study research that informs this paper: Michael Canares and Francois Van Schalkwyk from the Web Foundation; and Anirudh Dinesh, Auralice Graft, Juliet McMurren and Robert Montano at the GovLab. Editorial support for this paper was provided by Akash Kapur and David Dembo. The members of our Advisory Committee (see Appendix C) were a great resource to the project for which we are grateful. Finally, special thanks to the stakeholders we interviewed to gain on-the-ground and expert perspectives on the use of open data in developing economies, as well as the peer reviewers who provided input on a pre-published draft (see Appendix C).

This paper was authored by Stefaan G. Verhulst and Andrew Young of the GovLab.

OPEN DATA IN DEVELOPING ECONOMIES:

Toward Building an Evidence Base on What Works and How

Stefaan G. Verhulst and Andrew Young

Read MoreIntroduction

In 2009, the United States launched the data.gov portal. Since then there has been a rapid increase in the systematic opening of government data around the world. The 2016 Open Data Barometer,1 published annually by the World Wide Web Foundation, found that 79 of the 115 countries surveyed had official open data initiatives, and many others indicated imminent plans to establish such initiatives. Similarly, as part of the Open Government Partnership (OGP), a multilateral network established in 2011, some 70 countries have now issued National Action Plans, the majority of which contain strong open data commitments designed to foster greater transparency, generate economic growth, empower citizens, fight corruption, and more generally enhance governance. Approximately half of these countries are from the developing world,2 suggesting the uptake of open data is happening not only within economically advanced countries, but also in those less developed. All of this is part of a general move toward more transparent and innovative governance mechanisms, as emblematized by rising interest in notions of open government and open development.

The growing enthusiasm for, and use of, open data in developing economies leads to several questions about open data’s role in fostering development.3 Can open data bring about economic growth and social transformation? Can open data truly improve people’s lives in the developing world — and, if so, how and under what conditions? This paper’s goal is to take stock of what is known about open data’s use and impacts in developing economies, and to distill a theory of change based on existing theory and practice that can inform future open data use and research. This paper neither serves as a booster nor as a skeptic regarding the potential of open data in developing countries. Rather, it aims to sift through the evidence, draw out cross-cutting signals and insights from practice across developing economies when present, and start identifying the conditions under which open data appears able to work best, as well as those conditions that impede its potential.

Methodology

To formulate answers to the above questions and devise a theory of change, the authors undertook an extensive research effort that comprised a desk review of existing literature and identification of dozens of active open data projects around the developing world. From among these projects, the research team selected 12 case studies based on geographic and sector relevance. Each case study included further document review and consultations and interviews with project stakeholders over the course of three months. The outputs of these efforts and this final paper were reviewed and informed by an advisory group of open data for development experts and a group of open data peer reviewers. Throughout the paper, examples from these case studies (summarized in Appendix A) are employed to illuminate the real-world impacts of open data, when they exist, as well as the enabling and disabling conditions that play a role in determining whether such impact is positive, negative — or negligible.

In developing a change theory and identifying meaningful answers to the above organizing research questions on the impact of open data, this paper builds upon existing studies and analyses about the relationship between open data and development.4

Limitations

The primary objective of this research was to capture the universe of current narratives and evidence of open data for developing economies. We found that the literature remains largely focused on the potential of open data to bring about positive impacts. In many instances, the benefits of open data are celebrated despite little concrete evidence to prove that opening data has in fact created positive on-the-ground impacts at a meaningful scale. In addition, when evidence is being presented, little distinction is made between intent, implications, and impact. As such, this paper does reflect the positive narrative provided by the literature on open data for developing economies, but does so to help identify a meaningful signal in the noise, and provide an analytical framework to enable others to build on our work and further crystallize the true impacts and drivers of successful open data initiatives in developing economies. Our aim is to enable the field to move from ideology to evidence; we see this paper as an initial step toward that end.

Before considering the (variable) evidence, it is important to note that “developing economies” are not uniform or monolithic. Our analysis focuses particularly on low- and medium-income countries, spread primarily across Africa, Latin America, and Asia. We do believe that some of the examples and evidence presented could be helpful in informing discussions and efforts underway in other contexts and countries. But questions of replication and scalability are complex — particularly when considering technological interventions — and we make no claims that the lessons offered here are universal, or even universally applicable across the diversity of countries that could be classified as low or medium income. So although this paper seeks to provide a set of testable research-driven premises and useful recommendations for open data practitioners and funders working across the developing world, it remains essential to always consider a country’s local context and needs when seeking to replicate success stories or implement recommendations found in this paper.

Paper Contents

In essence, the paper seeks to answer the following key questions

- What makes open data uniquely relevant to developing economies?

- How can the impact of open data in developing economies be captured and evidence be developed?

- How can open data be leveraged as a new asset for development?

Toward that end the paper begins, in Part I, by providing a brief assessment on the theories and narratives of open data in development. In Part II, we present a change theory and a logic model to capture and develop evidence on open data in developing economies; these focus on enabling and disabling conditions, seeking to understand what makes open data projects work — or fail — to guide developing and funding open data initiatives in developing economies. Part III builds on the logic model presented in Part II with a focus on taking stock of open data’s impacts across various development sectors. The paper concludes with a set of key take-aways and recommendations for aid organizations, governments, private sector entities, and others that are considering replicating or using open data as an asset for development.

Read MoreI. What makes open data uniquely relevant to developing economies?

What is Open Data?

In this paper, open data is defined as follows:

Open data is publicly available data that can be universally and readily accessed, used and redistributed free of charge. It is structured for usability and computability.5

Not all forms of data shared actually possess all the attributes included in this definition, nor do they necessarily conform to all the principles found in the Open Data Charter.6 In many ways, this is a gold-standard definition of open data, an important target to work toward. In fact, the openness of data exists on a continuum, and many forms of data that are not strictly “open” in the sense defined above are nonetheless shareable and usable by third parties. It is this broader sense of “open” that is used in this paper.

Open data exists in a wide variety of fields and domains. Three sectors in particular are responsible for producing the bulk of open data: governments, scientists, and corporations. In this paper, we focus mainly on the release and use of government data. We acknowledge, however, the importance and often untapped potential of more open access to science data and corporate data. Those other data sources, as well as crowdsourced data collection are also often mashed up with open government data, supplementing official public datasets to create new insights, opportunities, and impacts as a result. In what follows, we deconstruct the main reasons why open government data matters to developing economies.

The literature on open data reflects considerable enthusiasm about the potential for open government data in development. For example, a recent report published by the Open Data for Development Network suggests that open data is central to the development community’s goals of “enabling widespread economic value, fostering greater civic engagement and enhancing government transparency and accountability to citizens.” The report goes on to argue that “open data is increasingly recognized as a new form of infrastructure that is transforming how governments, businesses, and citizens are organized in an increasingly networked society.”7 We do find some evidence to support such enthusiasm: across sectors, we see signs that open data can indeed spur positive economic, political, and social change. On the other hand, we also find grounds for caution; the impacts of many of the projects we examined remain largely aspirational or speculative, and some cases even led to harms (or potential harms). Although the real-world impacts of open data in developing economies remain emergent, it is important to distill these early lessons and develop a frame of analysis to support the current window of opportunity to increase access to data sources — a window that is likely to close absent any further evidence of open data’s impact or a better, more targeted description of the value proposition and change theory driving the field.

What makes open data uniquely relevant to developing economies?

We live in an era of big data. Every day, an unprecedented amount of information is being generated by an ever-increasing diversity of devices and appliances. Today, a growing consensus exists that this data, if applied correctly, and with attention to the attendant risks, can help spur positive social change. Sometimes called the “data revolution,”8 this new paradigm often fails to distinguish between the benefits of data per se and the complementing benefits of unlocking government data.9

Based on our examination of the narratives and evidence provided in the existing literature, six distinguishing features seem to be credited to open data. Although these characteristics are unique to open data, in many cases, they would not be possible without a broader data, technology, and innovation ecosystem. Across our case studies, we’ve seen that the existence of a strong information and communication technology for development (ICT4D) sector in a country, for example, tends to result in higher impact, more quickly developing open data efforts.

With the understanding in mind that open data must exist in a strong ecosystem, the six distinguishing features that are most quoted with regard to open data in a development context include:

Scrutiny

Because open data is subject to greater scrutiny and exposure than inaccessible institutional data, there is potential for enhanced review and improvement of government data quality (e.g., by data-literate civil society groups or other crowdsourced methods). This can result in more useful data — again, a benefit that is relevant in less developed countries and societies, where data is scarce, and of limited quality and usefulness.10

Equality

Open data can lead to an inherently more equitable and democratic distribution of information and knowledge. This is a key intended benefit in all countries, but particularly salient in many developing economies that struggle with large socio-economic and digital divides.11 It is important to keep in mind, however, that the lack of Internet penetration and access to tools for using and accessing open data still present challenges in many contexts — and, indeed, such technological inequities can be further entrenched through open data in some cases.

Flexibility

Open data is open with regard not only to the information it contains, but also to its format. This means that, when released in a usable manner, open data can be easier to repurpose and combine with other pieces of information than data institutions fail to make accessible, which in turn means that it is more flexible, with secondary uses that are likely to yield innovative insights. This is true of data from all sectors, but perhaps especially of government data, which often exists in vast, untapped silos; opening that data (turning it “liquid”) can play a key role in generating new insights and policies.12 Such liquidity can only become a reality if data, and the tools used to manipulate it, are interoperable and adhere to agreed upon standards. Creating such technical capacity can, however, lead to opportunity costs and require significant upfront resource allocation on the supply side, potentially slowing progress at the outset.

Participation

By facilitating citizen participation and mobilization, open data can allow a wider range of expertise and knowledge to address and potentially solve complex problems. This quality of “open innovation” can allow resource-starved developing economies to access and benefit from the best global minds and expertise. It can offer a more participatory way of solving complex public dilemmas, with pathways toward more easily tapping into previously inaccessible knowledge (e.g., those related to social and economic development).13

Trust

Because it increases transparency and avenues for citizen oversight, unlocking data can lead to higher levels of accountability and trust throughout societies and countries.14 This “sunlight” or “trust” quality of open data can have powerful ripple effects, including incentives for better government practice, and the enhancement of the quality of public life and citizenship. Such increases to trust and accountability rely on meaningful data being made open, however, rather than governments participating in “open washing” where largely useless datasets are made accessible toward boosting institutional reputation.

Value Amplifier

Finally, it is now widely recognized that data is a new kind of asset or knowledge is a form of wealth. The opening of government datasets in a flexible and equitable manner can amplify the value of data thanks to data filling important data gaps felt in society. Though this attribute is important across the world, it may have a particularly important role to play in developing economies. In its 2016 World Development Report, The World Bank pointed out that technology can play an “accelerator” role in developing countries.15 But while the inherent scarcity of resources (data and otherwise) in the developing world increases the apparent value and potential impact of open data, cultural and political barriers to timely and well-targeted open data provision efforts could slow progress.

These narratives surrounding the open data movement reflect those associated with the cross-sector paradigm shift from closed processes to open ones, and how it applies to governance and development. Software, for example, is increasingly developed in an open source manner. With the rise of the collaborative coding platform GitHub, a notable driver,16 the open source movement, similar to open data, is seen to be providing for more equal and flexible ways to create and access code — resulting in distributed coders, not just tech company employees, creating and improving exciting new products. Similarly, businesses and governments alike are embracing open innovation techniques, posing opportunities to the crowd to provide input on important challenges and absorbing the best ideas — providing for enhanced participation and scrutiny, other features of open data.17 The emerging fields of open governance and open development (see Text Box 1) are also built on similar principles and techniques.

Open Government and Open Development

Open Governance/Government18

Definitions of open governance or open government vary not only across sectors but within them. Definitions focus to varying degrees on the key elements of transparency, citizen participation, and collaboration, among others, depending on the context.

Some illustrative examples of “open government” definitions19 include:

“The general availability of government information is the fundamental basis upon which popular sovereignty and the consent of the governed rest, subject to several important restrictions on this general rule (i.e., to allow for the carrying out of the constitutional powers of the Congress and the President; to protect the personal and property rights of individuals, corporations and associations; to acknowledge administrative complications as to whether to release, to withhold, or to partially release particular types of information under particular conditions; to protect confidentiality of communications internal to government; to acknowledge the difficulty of segregating information when parts of a document should be released and parts withheld).”20

- Wallace Parks

“Open Government Principle: Applying the right to know under the Constitution” (1957)

“Open government is defined as a system of transparency (information disclosure; solicit public feedback), public participation (increased opportunities to participate in policymaking), and collaboration (the use of innovative tools, methods, and systems to facilitate cooperation among Government departments, and with nonprofit organizations, businesses, and individuals in the private sector).”21

- White House

“Transparency and Open Government: Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies” (2009)

“Open government involves: Increasing the availability of information about governmental activities; Supporting civic participation; Implementing the highest standards of professional integrity through: Increasing access to new technologies for openness and accountability, information sharing, public participation, and collaboration.”22

- Open Government Partnership

Open Government Partnership Declaration (2011)

Open Development23

In the wake of open government taking hold as an organizing concept for improving and innovating governance, open development has evolved as a more networked and innovative pathway to improving international aid and development efforts. In a book on the topic, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) seeks to gain clarity on the contours of the field of open development.24 Their assessment of the theory and practice involves a number of key elements present in open development work, including:

- The power of human cooperation

- Sharing ideas and knowledge

- The ability to reuse, revise and repurpose content

- Increasing transparency of processes

- Expanding participation

- Collaborative production

Based on the examination of these strands of openness in development efforts from the World Bank, ONE, African Development Bank, and others, the IDRC authors conclude that the central idea behind open development is: “harnessing the increased penetration of information and communications technologies to create new organizational forms that improve the lives of people.”25

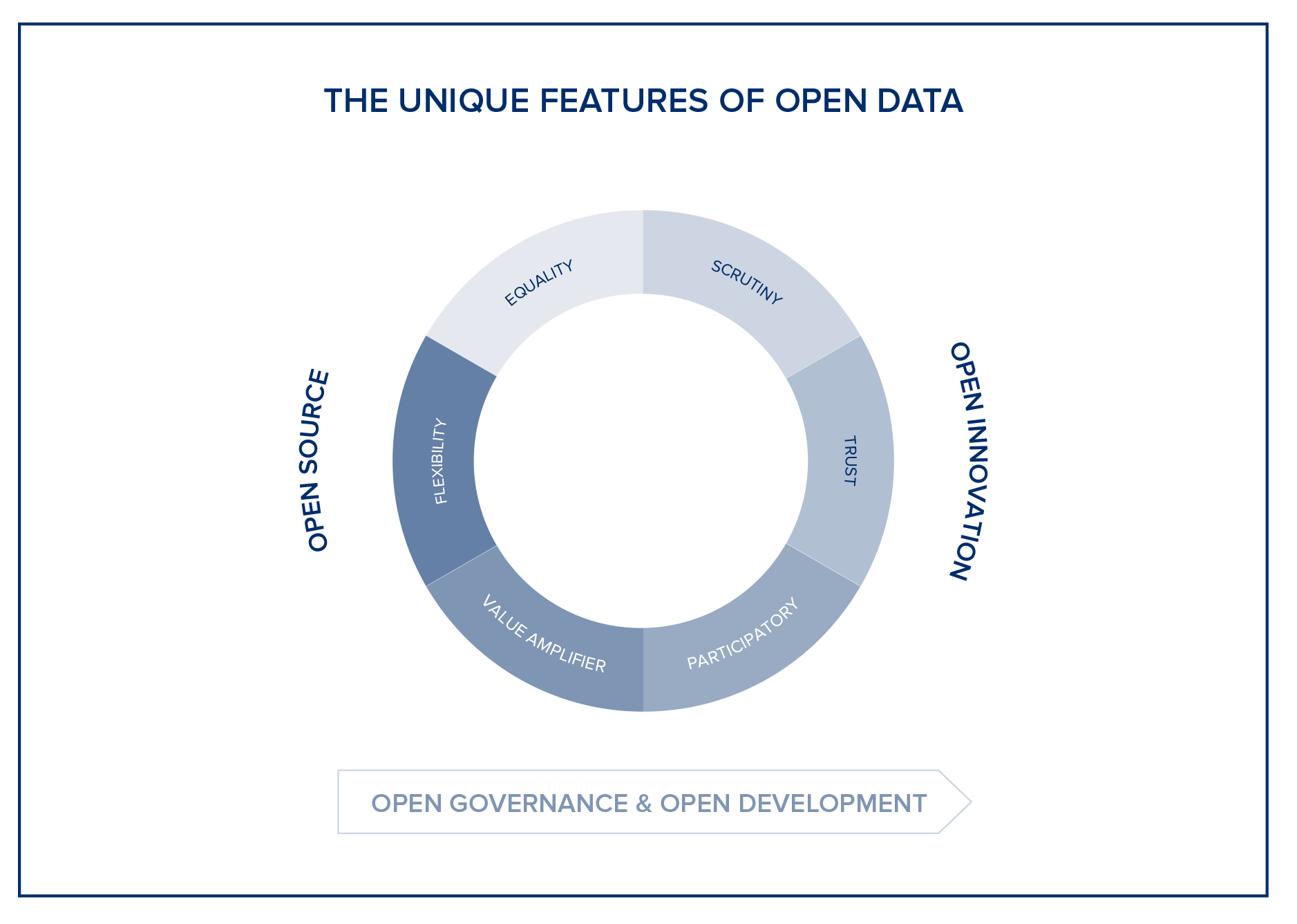

Data Life Cycle

An important insight from the emerging research and practice is that data is not “a thing” but involves a “process” — what we call a “data life cycle.”

How each stage of the data life cycle is implemented — from collection to processing and sharing; to analysis and using; and back to the start of the cycle again — will determine the value of data and who ultimately benefits. Disparities among those who collect and have access to data or have the capacity to make sense of the data can reinforce existing imbalances in power or influence. This is especially true in a developing economies context where the number of data holders and data scientists is more concentrated, and this smaller group is disproportionately empowered to make meaningful use of data. Within that context, opening datasets is often characterized as a force for democratization — engaging private and civil society actors, and, often indirectly as a result of intermediation, citizens themselves in analyzing and using data.26 As such, open data provides for unique efficiencies by leveraging civic-minded technologists (government and nongovernment), as well as entrepreneurs, to analyze, disseminate, and/or use data in a new, sometimes profitable way, as discussed more below.

On the other hand, each stage of the data life cycle contains risks. Risks are often the result of technological weaknesses (e.g., security flaws); individual and institutional norms and

standards of quality (e.g., weak scientific rigor in analysis); legal confusion or gaps; or misaligned business and other incentives (e.g., companies seeking to push the boundaries of what is socially appropriate). Although there are common elements across these risks, it is useful to examine them by separately considering each stage of the data value cycle.

When risks are not addressed at the initial stages of the value cycle (e.g., when dirty data is not cleaned at the collection stage) they may accumulate and lead to additional risks downstream (e.g., making flawed inferences from the data analysis due to inaccurate data). Therefore, it is important to consider potential risks not just at the points of opening data, but also at the data collection stage and evaluate those risks vis-à-vis the (potential) value of releasing the data. As such, to prevent harm, there may be a legitimate case — especially when there is a clear understanding of the purpose of the use and user — to share certain government datasets with those targeted audiences in a more protected manner to generate necessary insights while limiting the risks. We examine the risks introduced by open data efforts in developing economies in more detail in Part II.

II. How can the impact of open data on developing economies be captured and evidence be developed?

Many studies of open data are concerned with proving a case — either that open data can spur rapid social transformation (the positive case), or that it has a negligible or harmful effect (the negative case). In truth, the evidence is mixed and emergent; the impact of open data is, in fact, far more ambiguous. Rather than just asking Does open data spur development? we seek in this paper to also ask, How and under what conditions can it work?

To answer this question, we’ve examined a wide and variable range of attempts to provide evidence to develop a plausible “theory of change” that would explain the role of open data in development. Theories of change are important. A recent report from the United Kingdom’s Institute of Development Studies points to “the persistence of poorly articulated theories of change that fail to specify realistic causal pathways at the outset” in relation to transparency initiatives.27 Weak theories of change can lead to a variety of false assumptions and misconceptions when it comes to understanding how open data works; these, in turn, can lead to missed opportunities, spending inefficiencies, and a general failure to live up to open data’s potential.

A review of the literature shows that numerous pathways and theories of change have in fact been proposed. For example, a recent study conducted by IDRC, the World Wide Web Foundation, and the Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University cites at least thirteen “theories of change,” including open data’s ability to reduce transaction costs, generate new forms of economic growth and prosperity, generate new revenue models, and disrupt traditional business models.28 Others point to the social and environmental benefits of open data. For example, Martin Hilbert draws attention to the potential of opening geospatial-, education-, and housing-related information. Based on a review of 180 pieces of literature related to Big and Open Data, he concludes — with caveats we discuss further below — that open data does in fact contain true opportunities for development.29

Open Data in Developing Economies Logic Model

In what follows, we describe a change theory for open data using the Open Data in Developing Economies Logic Model (Figure 3).30 This model suggests that:

Open data (supply), when analyzed and leveraged by both governmental and non-governmental actors (demand), can be used in a variety of ways (actions and outputs), within the parameters established by certain enabling conditions (and disabling factors), to improve government, empower citizens and users, create economic opportunity and/or solve societal problems (impact).

It is important to reiterate, however, that these positive impacts are always subject to certain local, context-sensitive enabling conditions and disabling factors. While this logic model presents a general outline of how open data can work, Table 1, below, presents a more detailed explanation of how it interacts with various sector-specific opportunities and challenges to create genuine impact on the ground.

The logic model is built around the premise (informed by the case studies and primed for further experimentation and research) that higher impact open data projects are the result of matching the supply to the demand of data actors who can operationalize open data toward specific activities and outputs. These outputs and activities can, in turn, serve a broader and more diverse group of users and objectives.

Having a logic model allows for a more detailed analysis within and across sectors of open data toward providing a number of highly specific lessons about actors and conditions, opportunities and challenges.

| Input (Supply) | Actors (Demand) | Activity | Output | Use/Users | Indicators | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Open Government Data “Open data is publicly available data that can be universally and readily accessed, used and re-distributed free of charge. It is structured for usability and computability.” Including, for instance:

|

NGOs & Interest Groups Researchers and Academia Journalists and Media Outlets Donor Organizations Private Sector—Entrepreneurs and Corporations Government Officials |

Data Analysis (Methods) Presentation (Visualization) Aggregation and Commingling (Mashups) Dissemination —toward, for instance:

|

Decision Trees Maps Apps and Platforms Dashboards Process improvements Data-driven journapsm Infographics Searchable databases Policies Advocacy Alerts |

Other Government Agencies and Officials Nongovernment Actors including, for instance:

|

The outputs of open data have had several real-world effects, which can be assessed according to a number of indicators, for instance: Accountability

Improved service delivery:

Increased information sharing:

Enhanced decision-making capacity and choice:

Social mobilization:

Job creation:

Frugal innovation:

Economic growth:

Improved situational awareness:

More expertise and knowledge brought to bear:

Targeting interventions and tracking impact:

|

Improving Government

Empowering Citizens

Innovation and Creating Economic Opportunity

Solving Public Problems

|

|

Enabling Conditions and Disabling Factors

|

||||||

Examining the Open Data in Developing Economies Logic Framework

The logic model presented in Figure 3 above describes the elements in place across the lifespan of an open data initiative, from the initial input or supply of data through its use and impact, with several enabling conditions and disabling factors influencing impact. We explore each of the elements introduced in the table in more detail below, with attention to the types of impact and the enabling conditions and disabling factors that inform the Periodic Table of Open Data Elements.

Input (Supply)

A diversity of data types make up the supply side of open data in developing economies and, as the input, plays a key role in determining the ultimate impact. Data types being made available in developing countries range from information about the planet, such as geospatial and weather information, to information about the workings of government itself, like financial and administrative data. Of importance within a developing country context, involves data that is collected and potentially supplied by international (donor) organizations and civil society (often through crowd-sourced means) that may complement the supply of domestic government data. Much of the focus in the early days of open data (in both developed and developing economies) has fallen on improving the supply side of open data, with the Open Data Charter and Open Government Partnership, for example, pushing government data holders to make certain types of data accessible according to a number of principles and in a standardized way.

Actors (Demand)

As the global open data ecosystem matures, a greater focus is being placed on understanding the demand side of open data — the actors who will make use of the information the governments released. As the supply side of open data continues to improve thanks to international standardization efforts, including the Open Data Charter and advocacy at the national and regional level, the demand side stands to benefit through greater engagement of existing demand-side actors, and the identification of additional stakeholders who could make use of that information. Some of the key yet distinctive segments or constituencies (often with different interests and needs) on the demand side of open data include nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including not only government watchdog groups but also service providers, researchers and scholars, data-driven journalists, entrepreneurs and businesses, and government officials themselves who benefit from more liquid data that has escaped internal silos.

Activities

The activities enabled by access to open data are in many ways only limited by the imagination and skills of the actors on the demand side of the equation. Some of the most common ways that open data is used include data analysis to uncover new insights, presentation and visualization to make the information more comprehensible, aggregation and commingling of multiple datasets to gain a more multi-faceted view of an issue, and eventually dissemination of processed open data toward benchmarking efforts, hotspotting (e.g., data-driven crime or healthcare maps), or informing future resource allocation decision making.

Output

Like the activities open data enables, the output of processed open data can take any number of forms depending on the problem or opportunity the data is meant to address and the priorities of the actors on the demand side. Although the output of open data initiatives is often some form of data or technology — such as searchable databases, information dashboards or smartphone applications — they can also take the form of evidence-based policies, advocacy, or activism efforts or data-driven journalism pieces.

Use/Users

The existence of actors on the demand side of open data and users of the open data-driven outputs those actors create complicates the lifespan of open data and makes clear the need for responsiveness and feedback loops on the supply side. In many cases, the types of actors representing the demand side of open data are also present as users of open data outputs — such as NGOs or journalists. The community of user includes a broader swath of the population, however, with individuals and entities that lack any data science capabilities still able to make use of the outputs of open data — whether in the form of smartphone weather applications, data-driven infographics in the newspaper, or government process optimizations.

Indicators

In many ways, open data is a double-edged sword. How open data is made accessible to the public ensures that anyone can use open data for any reason. It also means that identifying those usages and capturing their impacts is extremely challenging, especially for resource-strapped governments. To gain some meaningful sense of the impact of open data releases, data holders can seek to develop indicators tied to the problems open datasets stand to address. After the release of open data on the financial dealings of government officials, for instance, an uptick in court cases on corruption could provide a window into open data’s impact on accountability. Similarly, the creation of more data-driven startups, increased investment from international donors, or increases in hiring among technology companies that use (or are likely to use) open data can act as indicators of open data’s effect on economic development. Especially in developing economies where government resources are often limited, meaningfully capturing the impacts of open data through indicators of success will likely prove essential for maintaining the political will needed for open data efforts to be sustainable.

Types of Impact

As reflected in Table 1, our research indicates that open data has four main types of impact, and that each type of impact requires different indicators. Although the four types of impact described below provide a framework of analysis, it is also important to understand that these types of impact can manifest in different ways, and some projects might seek to achieve more than one type of impact. In the discussion below, we point to a diversity of open data initiatives aimed at having a positive effect in one or more of these impact areas, but in some cases, impact remains largely aspirational; in others, impact was negligible, or in fact, negative. Rather than focusing exclusively on gold-standard open data projects with unquestionable and consequential on-the-ground impacts — like the oft-referenced Global Positioning System or opening of weather data in the United States — we examine initiatives across the spectrum of impact to develop a more detailed understanding of the current reality for open data in developing economies, and more importantly, to provide testable premises of how to create an impact based on lessons learned from efforts to date, even some efforts that have not (yet) created major positive impacts.

To be sure, much of the evidence provided below is emergent, and in some cases largely speculative. Collecting and organizing these signals of what is known (and believed) about open data for development, however, provides for a systematic understanding of the current field, and informs more strategic, analytical assessments of open data’s impact going forward. So although the evidence here is unquestionably variable — ranging from concrete, clearly demonstrable on-the-ground impacts to largely ideological assertions of impact — they provide a frame for understanding the field and taking the next step toward meaningful impact assessment.

1. One of the most consistent ways in which open data has an impact on development, across countries and regions, is in improving governance. This impact manifests in several ways:

- Greater transparency and citizen involvement can make governments more accountable to their citizens.

- A focus on data use and data-driven decision making engendered by the institutional process of opening data (i.e., cleaning and making liquid government datasets) can result in better and more efficient service delivery.

- In addition to making data accessible to entities outside of government, open data efforts can increase information sharing between departments and agencies within government, improving coordination and knowledge-sharing.

Emergent Evidence:

- Elections in Burkina Faso: To ensure elections in Burkina Faso were conducted fairly, poll results were made available in real time via an official election website, which tracked candidates leading in each of the provinces. This project, run by the Burkina Open Data Initiative (BODI, http://data.gov.bf/about) with the support of the ODI, sought to promote democracy and trust between Burkina Faso’s citizens and elected officials. For a country in transition like Burkina Faso, opening electoral data was seen as an important first step toward establishing longer term political stability and citizen trust in the electoral process, though the number of citizens or organizations who actually accessed and acted upon the data is unclear.31

- Elections in Indonesia: In a similar initiative, Indonesia’s Kawal Pemilu (“guard the election,” in Indonesian) was launched in the immediate aftermath of the 2014 presidential elections, as the country was riven by political polarization and the two leading contenders for the presidency traded allegations of vote rigging. A globally dispersed group of technologists, activists, and volunteers came together to create a website that would allow citizens to compare official vote tallies with the original tabulations from polling stations. These tabulations were already made public as part of the Elections General Commission’s commitment to openness and transparency. Kawal Pemilu’s organizers, however, played a critical role in assembling a team of over 700 volunteers to digitize the often-handwritten forms and make the data more legible and accessible. The site was assembled in a mere two days, with a total budget of just $54. Not only did the site enable citizen participation in monitoring the election results, but Kawal Pemilu’s vote tallies also played an important role in court hearings confirming the election winner.32

- Data Journalism in Kenya: In Kenya, journalists leveraged open data to report on a “freeze” in the dissemination of welfare support to the elderly and disabled. The freeze was traced back to a government failure to build an effective system for distributing such funds and, as a result, a significant amount of public money went missing. Media attention and public pressure that grew out of this open data-driven journalism effort led to an audit of the program and the implementation of reforms.33

2. Open data also has a powerful role to play in empowering citizens. This role is evident in several ways:

- With more access to information in hand (including information on, for example, health care or education choices), citizens can have improved decision-making capacity and choice.

- As a result of increased transparency, open data can act as a social mobilization tool when information made available to the public can inform advocacy efforts, including those related to corruption or perceived corruption, consumer advocacy, or health care and other service delivery.

Emergent Evidence:

- Follow the Money Nigeria: In Nigeria, a consortium of activists, journalists, researchers and NGOs use open data to track and visualize government expenditures. Based on knowledge drawn from open data regarding current spending practices, the group successfully pushed the Nigerian government to allocate $5.3 million to help address a lead poisoning crisis in the village of Bagega that affected thousands of children. Follow the Money Nigeria in fact demonstrates how open data can both improve governance (as a result of enabling better, more evidence-based policy decisions) and empower citizens to have an impact on their communities. 34

- Seeking to Improve Voter Turnout in Kenya with Open Data: Kenya’s national Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) released information about polling center locations on its website in the lead up to Kenya’s 2013 general election. The information, however, was difficult to access and reuse. Seizing on the gap between opening government data and citizens’ actual ability to use that data, two Code 4 Kenya fellows conducted an experiment in unlocking government data to make it useful to the public. The fellows scraped the released IEBC data and built a simple website where it could be more easily accessed. The result was the initial version of GotToVote! a site that provided citizens with voter registration center information, and also helped them navigate the sometimes complex world of registration procedures. This first version was developed in just 24 hours at minimum cost, garnered over 6,000 site visits in just its first week of existence, and has since been replicated across sub-Saharan Africa.

- Social Movements in Brazil: The availability of open data has helped to inform the community organizing and advocacy efforts of several social movements in Brazil. Efforts to fight the use of pesticides latched onto the fact that “each Brazilian citizen is exposed to [5.2 liters] of pesticides every year.” Similarly, an effort to fight school closures has rallied around the 24,000 schools that open data shows have been closed over the last 10 years. Efforts to fight violence against women and the consolidation of land ownership are similarly using open data to aid in their advocacy. There’s little causal evidence that these efforts directly created significant policy impact, however, though the resignation of the Minister of Promotion of Racial Equality is credited to open data-driven reporting and advocacy.35 So although these advocacy efforts demonstrate how open data can empower citizens and advocates through access to important factual information, more work needs to be done (and responsiveness in the public sector must be engendered) to create more direct, tangible impacts.36

3. Under the right conditions, open data can help create economic activity. If harnessed properly, this is a particularly important form of impact in developing economies. Our case studies indicate that open data can have a positive impact on economic activity in the following ways:

- As the global economy becomes increasingly reliant on data and information, the accessibility of open data can enable business creation, foreign investment, and meaningful job creation.

- Open data is increasingly seen as a new business asset but, unlike many such assets, it is available free of charge, opening the door to more frugal innovation efforts in the private sector.

- More than just an asset to individual businesses or entrepreneurs, many predictive analyses have pointed to open data’s potential for creating more systemic and far-reaching economic growth, particularly when commingled with proprietary data held by private sector entities.37

Emergent Evidence:

- Market Research in Kenya and Nigeria: Sagaci Research is a market intelligence firm based in Kenya that works across countries in Africa. The firm’s strategic knowledge offerings — spanning sectors like consumer goods, agriculture, and telecom — are built from researchers and field surveyors active across Africa and, importantly, open census and national statistical data from the Kenyan and Nigerian governments. According to the Sagaci website, 90 percent of its clients have pursued follow-on work with the firm, demonstrating the value of its open data-driven offerings.38

- Data Mapping Consultation in India: Excel Geomatics is a private consultancy firm that leverages open data to provide geospatial insights to private and public sector clients. The company’s offerings — including ward maps of more than 700 towns and cities and satellite image-enabled population distribution maps — would not be possible without access to data from the Indian census, as well as publicly accessible village and district boundary maps. Importantly, Excel Geomatics uses the Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) and ASTER database from NASA for its products and services — demonstrating how the opening of data in developed countries often creates impacts far afield.39

- Open Data to Benefit Tourism in Jamaica: Like much of the Caribbean, the Jamaican economy is spanly dependent on the health of its tourism industry. Influenced by the rise of all-inclusive resorts and a general disincentive for tourists to stray far from a few highly trafficked areas, tourists rarely experience much of Jamaica’s unique culture, and the economic benefits of tourism are often concentrated in a few areas. To increase tourism, spread its positive impacts and provide useful skills to citizens, a community mapping project40 combined open government data with crowdsourced, volunteer-collected mapping data to enable the more participatory development of the tourism sector. Built around open tourism data and the engagement of government agencies, civil society organizations, developers, and an interested group of community mappers, the initiative has created new artifacts aimed at better spreading the economic impacts of the tourism industry in Jamaica, though impact remains primarily aspirational.41

4. Finally, open data’s impact is evident in the contribution it makes to solving public problems. Open data can help address complex problems in the following ways:

- Especially in crisis situations where geospatial information can prove essential,42 open data can play a role in improving situational awareness.

- In some developing countries, government is the primary data holder and data user, limiting the number of people capable of creating value with data. The accessibility of open data can help to bring a wider range of expertise and knowledge to bear on public problems.

- In many cases the result of improved situational awareness and more expertise brought to bear, open data can play an important role in targeting interventions and meaningfully tracking impact.

Emergent Evidence:

- Stopping Deforestation in Brazil and Indonesia: To monitor deforestation in Brazil and Indonesia, Global Forest Watch consolidates satellite imagery datasets to monitor global deforestation in real time. Monitoring on this scale has produced several observable positive effects. For instance, data from the project has been used in legal proceedings related to illegal logging. Although causation cannot be proved directly, deforestation has declined in both countries — deforestation in Indonesia is at its lowest levels in a decade and has declined by 18 percent in Brazil.43 It is important to note that prior to this project, deforestation levels were consistently rising in both nations. The Indonesian government also uses GFW to monitor forest and peat fires and target response.44 In Brazil, firefighters have reduced their response time to forest fires from 36 hours to 4 hours. This project is a forceful demonstration that intelligent use of open data can be used for successful advocacy — and could even provide additional benefits that may not have been anticipated.

- Fighting Ebola in Sierra Leone: In the parts of West Africa affected by the Ebola epidemic, roads, village names. and villages were missing on many online maps. OpenStreetMap (OSM), a free, crowdsourced mapping tool provided critical mapping information to Sierra Leone’s National Ebola Response Centre (NERC), the United Nation’s Humanitarian Data Exchange, and to the Ebola GeoNode to assist them in coordinating public health strategies in response to the epidemic. The OSM data was then often mashed up with open data from affected governments and international organizations. Although the direct impact of open data in the Ebola response was difficult to empirically measure, those working on the ground during the response made clear that providing missing data in open formats played an important role in fighting a complex epidemic and coordinating relief efforts of those working in a chaotic, fast-developing context.45

- Targeting Disaster Risk Funding in the Philippines: The Philippines was one of the eight founding members of the Open Government Partnership launched in 2011, endorsing an Open Government Declaration to commit to open data. As part of its commitment, in 2014 the Philippine government launched data.gov.ph, which publishes data from government agencies for the public to access. Though some federal agencies have been hesitant to disclose their data in an open and accessible way, at the local government level the open data initiative is making more headway. The disclosure of spending data in Bohol province, for example, allowed civil society groups to notice that insufficient funds were allocated to disaster risk reduction projects. As a result, organizations are now drafting new disaster-reduction proposals to lobby the government to provide more support to this area.46

- PakReport Crisis Mapping: In the wake of the worst flooding in Pakistan in decades, several crisis mapping organizations (led by PakReport) teamed with relief organizations to map affected areas in real time. This project was a piece of a broader trend toward crisis mapping, particularly after natural disasters. Collaboration of this kind allows aid organizations to survey areas that may be difficult to landscape because of the disaster and correctly understand where needs are greatest and what kind of assistance populations across the affected area require. The efforts of the PakReport team demonstrate the complicated nature of international disaster relief and the need for comprehensive and proactive data responsibility assessments. Pointing to the risks and unintended consequences of open data, PakReport was forced to restrict access to its crowdsourced maps, which were intended to be open and freely accessible, after the Taliban threatened to attack foreign aid workers in the country, whose presence they deemed “unacceptable.”47

Enabling Conditions and Disabling Factors

Table 2. Periodic Table of Open Data Elements. View interactive periodic table here.

Based on the existing literature (see Appendix D) and case studies, we have developed a Periodic Table of Open Data Elements (Table 2 above) detailing the enabling conditions and disabling factors that often determine the impact of open data initiatives. Although the importance of local variation and context is, of course, paramount, current research and practice shows that the elements included in five central issue categories — Problem and Demand Definition, Capacity and Culture, Partnerships, Risks, Governance — are likely to either enable or disrupt the success of open data projects when replicated across countries.

As discussed above, there is a large variability as it relates to evidence of open data’s impact, so we provide these enabling conditions and disabling factors not as a concrete, certain drivers of success or failure, but as an aggregated set of premises to be tested as the field of practice and research of open data in developing economies continues to expand and mature. We examine these enabling conditions and disabling factors in more detail here.

The Challenge of Scaling and Replication

Much of this paper, including the above, seeks to identify cross-cutting lessons for open data projects — either in the form of opportunities or challenges. As noted, however, it is important to keep in mind the diversity that exists within the broad category of “developing economies.” Differences in culture, economic, and political environments, as well as many other variables, can have a profound effect on the success or otherwise of open data projects.

In many ways, this is another challenge facing stakeholders — and perhaps the most intractable: the difficulty of finding an appropriate balance between universal lessons and certain, locally embedded conditions, when seeking to scale and replicate open data projects. The preceding discussion and the sector-specific examples detailed in Section III do suggest that certain enabling (and disabling) conditions have wide applicability — e.g., the need to include intermediaries and civil society groups,60 or the paramount importance of capacity and resources.

Perhaps the most critical element for scaling and replication found in the Periodic Table is Metrics: the need for open data projects should be evidence based, with clearly defined metrics and standards to evaluate performance. Only with those metrics in place can the applicability or appropriateness of lessons or principles be determined — and only then can the success or failure of projects be established. When making any funding or design decisions, it is essential to take a fine-grained approach that pays close attention to the empirical evidence, sifting out what works and what does not. That is a key goal of the 12 case studies that accompany this landscaping paper; we have tried to build a ground-up, highly empirical picture of open data projects in the developing world.

Read MoreIII. The Realized and Intended Impacts of Open Data in Developing Economies across Sectors

The preceding section has described a logic framework that examines the different components that determine how open data could create an impact. It identifies both enabling and disabling factors for open data initiatives that seek to create four different types of impacts, and expands on them in a practitioner-focused Periodic Table of Open Data Elements. This in effect allows us to create more particular or fine-grained theories of change for each sector and area of impact. In this section, we consider the emerging (and again, variable) evidence of open data’s impact on specific sectors that are relevant to the development context. We focus on six sectors: Health, Humanitarian Aid, Agriculture and Nutrition, Poverty Alleviation and Livelihoods, Energy, and Education.

For each sector, we describe illustrative examples of open data’s use in developing economies. The cases described here are provided to offer a glimpse into the current field of practice. Some sectors have seen more notable (and novel) applications of open data than others, and some of the examples described here have had little impact to date, or represent instructive failures. But even these lower impact initiatives can aid in identifying testable premises to guide future practice and experimentation. Considered together, these over-arching and sector-specific theories of change build a more complete and detailed matrix of how and under what conditions open data impacts development, providing a set of hypotheses for further research and experimentation.

Health

Improving Governance

The health sector is a major recipient of public funds and international aid, particularly in developing countries61. Increasing the transparency of this large area of government expenditure in turn increases accountability, helping ensure resources efficiently and adequately target public health needs.

Empowering Citizens

Accessing quality-of-care information for different health care providers can bolster citizens’ ability to make informed choices regarding their service providers62. Data on corruption or malpractice in the health care system can particularly enable evidence-based advocacy efforts for patients.

Innovation & Creating Opportunity

As the health sector becomes increasingly data-driven, open data can help spur job creation and the establishment of new service models as a result of both making more information available on the supply side, and using newly accessible health data on the demand side. Though concerns regarding the potential for technology and automation to negatively impact employment also exist.

Solving Public Problems

Especially in the wake of health crises (such as the Ebola outbreak in West Africa or mosquito-borne epidemics in India, for example63), access to data across institutions on the availability and location of health resources and on emergent health outcomes can play an important role in addressing major epidemics or ingrained public health concerns.

Examples

Predicting Dengue Outbreaks in Paraguay with Open Data

Description

Since 2009, dengue fever has been endemic in Paraguay. Recognizing the clear problem at hand, and the lack of a strong system for communicating dengue-related dangers to the public, the National Health Surveillance Department of Paraguay opened data related to dengue morbidity. Leveraging this data, researchers created an early warning system that can detect outbreaks of dengue fever a week in advance. The data-driven model can predict dengue outbreaks at the city-level in every city in Paraguay. Importantly, the system can be deployed in any region as long as data on morbidity, climate, and water are available.

Logic Framework Components

Input

Open health, climate, and water data

Actors

Researchers and academia

Activity

Data analysis

Output

Process improvements, alerts

Users

Government officials, researchers

Indicators

Accuracy of data-driven predictions

Intended Impact

Solving public problems

Code for South Africa Cheaper Medicines for Consumers

Description

In 2014, Code for South Africa, a South Africa-based nonprofit organization active in the open data space, took a little known dataset from the national Department of Health website and created the Medicine Price Registry Application (MPRApp), an online tool allowing patients (and their doctors) to make sure that they aren’t being overcharged by their pharmacies. With no marketing or promotions to speak of, MPRApp has had an impact on the lives of a few South Africans; with a more sustainable model and increased awareness of MPRApp, particularly among trusted intermediaries in the health sector, it could provide more patients access to cheaper medicines.

Logic Framework Components

Input

Open medicine data

Actors

NGO

Activity

Dissemination

Output

Searchable database

Users

Citizens, health service providers

Indicators

Money saved by individuals

Intended Impact

Empowering citizens

Open Health Data in Uganda

Description

In Uganda, open data initiatives are being used in an attempt to improve health outcomes and revolutionize a health care industry marred by staff shortages, lack of resources and corruption. The Kampala-based organization CIPESA has collaborated with a local media organization, Numec, to create the iParticipate project (http://cipesa.org/tag/iparticipate/), which analyzes open government data, and trains citizens and intermediaries to use that data toward empowering citizens to play a bigger role in health governance. Similarly, the Women of Uganda Network (http://wougnet.org), which trains women to use information technology, created an online platform to collect and document information relating to poor health care services. Both these initiatives allow citizens to scrutinize and lobby the public health care sector, aiming to improve its efficiency and ensure that services respond to the needs of citizens in a robust manner.

Logic Framework Components

Input

Open health data

Actors