The Global Impact of Open Data

United Kingdom's Open Public Services Network

New Strategies to Close the Data Gap

by Becky Hogge

Reference

1 Prime Minister’s Office. (2010, May 29). PM’s podcast on transparency. Retrieved from gov.uk: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pms-podcast-on-transparency

2 digitalhealth.net. (2007, July 18). DH blasted for ‘back room deal’ with Dr Foster. Retrieved from digitalhealth.net: http://www.digitalhealth.net/news/22819/

3 Open Public Services Network. (2013, September). Empowering Parents, Improving Accountability. Retrieved from https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/empowering-parents-improving-accountability/

4 Open Public Services Network. (2013, September). Empowering Parents, Improving Accountability. Retrieved from https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/empowering-parents-improving-accountability/

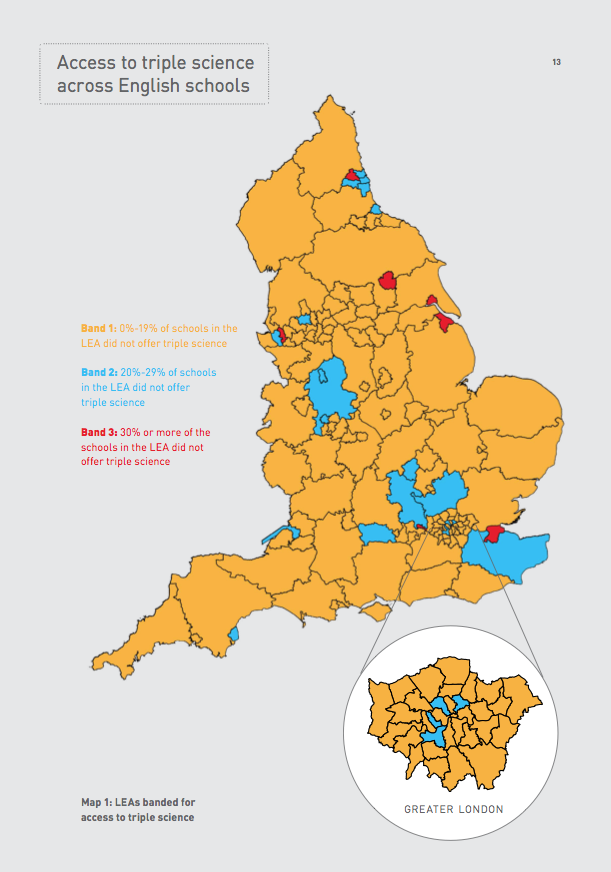

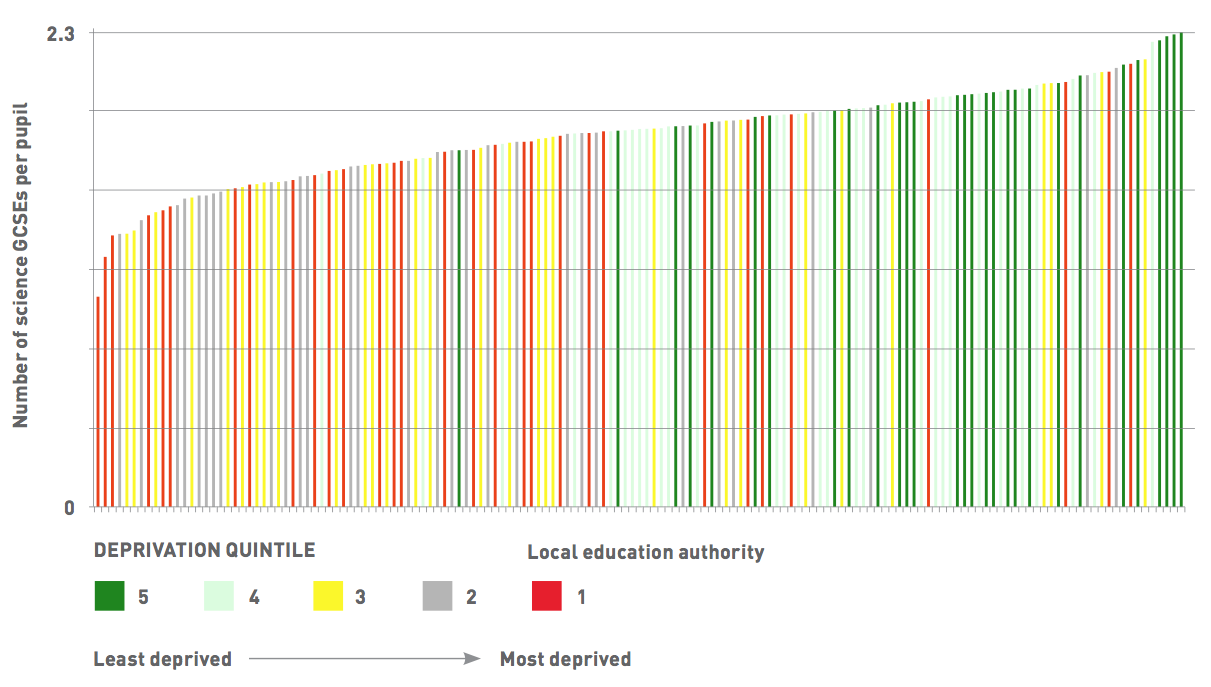

5 Open Public Services Network. (2015, February). Lack of options: how a pupil’s academic choices are affected by where they live. Retrieved from https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/lack-of-options-how-a-pupils-academic-choices-are-affected-by-where-they-live/

6 Department for Education. (2013). The national pupil database: User guide. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/261189/NPD_User_Guide.pdf

7 Department for Education. (2013). The national pupil database: User guide. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/261189/NPD_User_Guide.pdf

8 Open Public Services Network. (2013, September). Empowering Parents, Improving Accountability. Retrieved from https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/empowering-parents-improving-accountability/

9 Interview, Charlotte Alldritt, Director, Open Public Services Network.

10 Hansen, K., Joshi, H., & Dex, S. (2010). Children of the 21st century: The first five years. Policy Press.

11 Interview, Charlotte Alldritt, Director, Open Public Services Network.

12 Adams, R. (2013, September 11). School database lets parents compare GCSE results by subject. Retrieved from The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/education/2013/sep/11/school-database-gcse-results-subject

13 Open Public Services Network. (2015, February). Lack of options: how a pupil’s academic choices are affected by where they live. Retrieved from https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/reports/lack-of-options-how-a-pupils-academic-choices-are-affected-by-where-they-live/

14 Cabinet Office. (2013, January 24). Prime Minister David Cameron’s speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/prime-minister-david-camerons-speech-to-the-world-economic-forum-in-davos

15 World Bank. (n.d.). Education Sector uses of open data. Retrieved September 30, 2015, from World Bank: https://finances.worldbank.org/Reference/Education-Sector-uses-of-open-data/grcz-ymf2

16 Coughlan, S. (2015, February 11). Pupils in some areas are not offered ‘vital’ GCSEs. Retrieved from BBC News: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-30983083

17 Times Educational Supplement. (2015, February 11). Pupils in poor areas denied chance to study science and foreign languages, says study. Retrieved from Times Educational Supplement: https://www.tes.co.uk/news/school-news/breaking-news/pupils-poor-areas-denied-chance-study-science-and-foreign-languages

18 Nottingham Post. (2015, February 12). Nottinghamshire pupils ‘miss out on GCSE subjects’. Retrieved from Nottingham Post: http://www.nottinghampost.com/Pupils-miss-GCSE-subjects/story-26013138-detail/story.html

19 Bradford Telegraph and Argus. (2015, February 11). Fears over job prospects of Bradford pupils who fail to study languages at GCSE. Retrieved from Bradford Telegraph and Argus: http://www.thetelegraphandargus.co.uk/news/local/localbrad/11786686.Fears_over_job_prospects_of_Bradford_pupils_who_fail_to_study_languages_at_GCSE/

20 Sampson, L. (2015, February 11). Middlesbrough a ‘subject desert’: Pupils unlikely to take exams that could be vital to job prospects. Retrieved from Gazette Live: http://www.gazettelive.co.uk/news/teesside-news/middlesbrough-subject-desert-pupils-not-8626289

21 Harding, E. (2015, February 10). Schools ‘stop poorer GCSE pupils taking hard subjects’: Ploy to boost league rankings by denying access to exams including sciences. Retrieved from Daily Mail: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2948393/Schools-stop-poorer-GCSE-pupils-taking-hard-subjects-boost-league-rankings-denying-access-exams-including-sciences.html

22 Skidmore, C. (2015, March 24). HC Deb, 24 March 2015, c1324. Retrieved from TheyWorkForYou.com: http://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2015-03-24a.1324.2

23 For an interesting take on the role of evidence in policymaking, see Maybin, J. (2013, April 16). Experience-based policymaking. Retrieved from Institute for Government: http://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/blog/5671/experience-based-policymaking/

24 Gray, J., Bounegru, L., & Chambers, L. (2012). The Data Journalism Handbook: How Journalists Can Use Data to Improve the News. O’Reilly.

25 Interview, Roger Taylor, Chair, Open Public Services Network

26 Prime Minister’s Office. (2010, May 29). PM’s podcast on transparency. Retrieved from gov.uk: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pms-podcast-on-transparency

27 Thwaites, E. (2012, December 06). Prescription Savings Worth Millions Identified by ODI incubated company. Retrieved from Open Data Institute: https://theodi.org/news/prescription-savings-worth-millions-identified-odi-incubated-company

28 Wheeler, B. (2012, November 9). Government online data ignored by ‘armchair auditors’. Retrieved from BBC News: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-20221398

29 Freeguard, G., Munro, R., & Andrews, E. (2015, April). Whitehall Monitor: Deep Impact? Retrieved from Institute for Government: http://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/whitehall-monitor-deep-impact

30 Interview, Roger Taylor, Chair, Open Public Services Network

31 Interview, Roger Taylor, Chair, Open Public Services Network

32 Interview, Roger Taylor, Chair, Open Public Services Network

33 Interview, Roger Taylor, Chair, Open Public Services Network

34 Interview, Roger Taylor, Chair, Open Public Services Network

35 Interview, Roger Taylor, Chair, Open Public Services Network

36 For more on this see Conclusion. The contentious case of care.data, a scheme to centralise and share medical records previously held by individuals’ GPs that collapsed under the weight of public criticism in 2014, has shown at a minimum that policymakers should prioritise communicating with the public clearly about how their data will be shared and with whom, and actively seek, rather than assume, the public’s consent.