The Global Impact of Open Data

Open Contracting And Procurement In Slovakia

Establishing Trust in Government through Open Data

by Ali Clare, David Sangokoya, Stefaan Verhulst and Andrew Young*

Reference

1 Sipos, Gabriel. “Once Riddled with Corruption, Slovakia Sets a New Standard for Transparency.” Open Society Foundations. June 2, 2015. http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/once-riddled-corruption-slovakia-sets-new-standard-transparency.

2 Furnas, Alexander. “Transparency Case Study: Public Procurement in the Slovak Republic.” Sunlight Foundation Blog. August 12, 2013. http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/.

3 Sipos, Gabriel. “Once Riddled with Corruption, Slovakia Sets a New Standard for Transparency.” Open Society Foundations. June 2, 2015. http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/once-riddled-corruption-slovakia-sets-new-standard-transparency.

4 Kicina qtd. in Furnas, Alexander. “Transparency Case Study: Public Procurement in the Slovak Republic.” Sunlight Foundation. Sunlight Foundation Blog. August 12, 2013. http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/.

5 Furnas, Alexander. “Transparency Case Study: Public Procurement in the Slovak Republic.” Sunlight Foundation Blog. August 12, 2013. http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/.

6 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

7 Cienski, Jan. “Slovaks Protest over Corruption Claims” Financial Times. February 10, 2012. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/6fc1858c-48cd-11e1-954a-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3flczWkuI.

8 GovLab interview with Gabriel Sipos, Director of Transparency International, August 4, 2015.

9 GovLab interview with Gabriel Sipos, Director of Transparency International, August 4, 2015.

10 GovLab interview with Gabriel Sipos, Director of Transparency International, August 4, 2015.

11 Kenny, Charles. “Learning from Slovakia’s Experience of Contract Publication.” Center for Global Development. May 21, 2015, http://www.cgdev.org/blog/learning-slovakias-experience-contract-publication.

12 Sipos, Gabriel. “Once Riddled with Corruption, Slovakia Sets a New Standard for Transparency.” Open Society Foundations. June 2, 2015. Accessed July 14, 2015. http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/once-riddled-corruption-slovakia-sets-new-standard-transparency.

13 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

14 GovLab interview with Gabriel Sipos, Director of Transparency International, August 4, 2015.

15 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

16 Transparency International Slovakia. Face-to-face omnibus poll. February 3, 2015. Raw data.

17 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

18 Peer review input from Maria Zuffova, Slovak Governance Institute, November 29, 2015.

19 GovLab interview with Gabriel Sipos, Director of Transparency International, August 4, 2015.

20 “Transparency in Public Procurement Boosts Anti-Corruption Monitoring in Slovakia.” European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building. September 2, 2013. http://www.againstcorruption.eu/articles/transparency-in-public-procurement-boosts-anti-corruption-monitoring-in-slovakia/.

21 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

22 GovLab Interview with Eva Vozárová, Web & IT Lead, Fair-Play Alliance, June 23, 2015.

23 Furnas, Alexander. “Transparency Case Study: Public Procurement in the Slovak Republic.” Sunlight Foundation Blog. August 12, 2013. http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/.

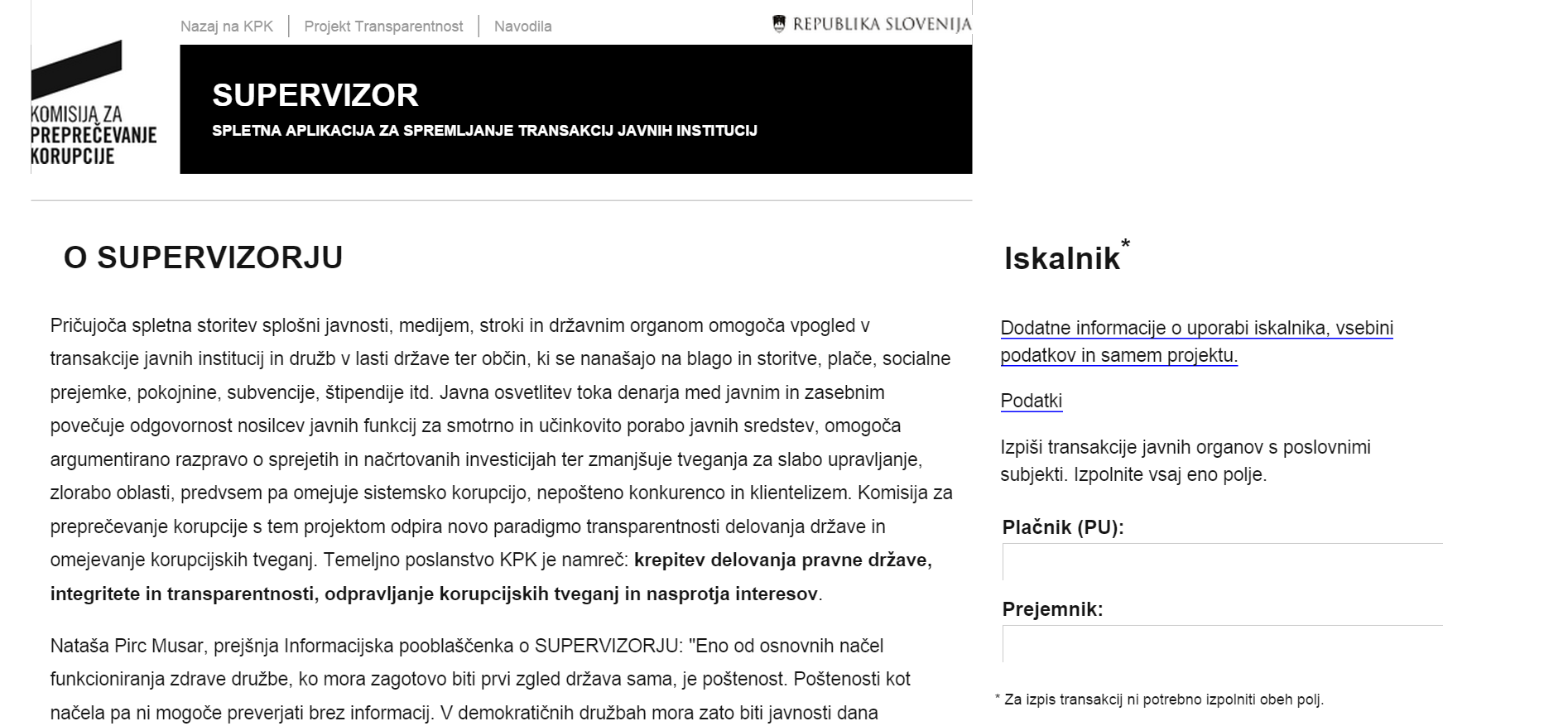

24 “Supervizor.” Supervizor–Commission for the Prevention of Corruption. 2011. Accessed July 14, 2015. https://www.kpk-rs.si/en/project-transparency/supervizor-73.

25 Del Monte, Davide, Ernesto Belisario, Andrea Menapace, Guido Romeo, and Lorenzo Segato. “Impact of Open Government on Public Sector Modernization Policies.” Transparency International Italia. 2014. http://www.eupan.eu/files/repository/20141215142852_RomeDG_-_14_-_Impact_of_Open_Government_on_PS_modernization_policies.pdf

26 Coldewey, Devin. “Slovenia Launches Supervizor, An Official Public Web App For Monitoring Public Spending.” TechCrunch. August 23, 2011. http://techcrunch.com/2011/08/23/slovenia-launches-supervizor-an-official-public-web-app-for-monitoring-public-spending/.

27 “Úvodem.” Informační Systémo Veřejných Zakázkách. 2013. Accessed July 14, 2015. http://www.isvz.cz/ISVZ/Podpora/ISVZ.aspx.

28 “Policy Statement of The Government of The Czech Republic.” Government of The Czech Republic. February 14, 2014. http://www.vlada.cz/en/media-centrum/dulezite-dokumenty/policy-statement-of-the-government-of-the-czech-republic-116171/.

29 Sipos, Gabriel. “Once Riddled with Corruption, Slovakia Sets a New Standard for Transparency.” Open Society Foundations. June 2, 2015. Accessed July 14, 2015. http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/once-riddled-corruption-slovakia-sets-new-standard-transparency.

30 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

31 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

32 GovLab Interview with Eva Vozárová, Web & IT Lead, Fair-Play Alliance, June 23, 2015.

33 GovLab Interview with Eva Vozárová, Web & IT Lead, Fair-Play Alliance, June 23, 2015.

34 Furnas, Alexander. “Transparency Case Study: Public Procurement in the Slovak Republic.” Sunlight Foundation Blog. August 12, 2013. http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/.

35 Sipos, Gabriel. “Once Riddled with Corruption, Slovakia Sets a New Standard for Transparency.” Open Society Foundations. June 2, 2015. Accessed July 14, 2015. http://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/voices/once-riddled-corruption-slovakia-sets-new-standard-transparency.

36 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

37 Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

38 Furnas, Alexander. “Transparency Case Study: Public Procurement in the Slovak Republic.” Sunlight Foundation Blog. August 12, 2013. http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/.

39 HES Data Quality Team. “The HES Processing Cycle and Data Quality.” Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2013. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/article/1825/The-processing-cycle-and-HES-data-quality

40 “Nations in Transit 2015 – Slovakia.” RefWorld. June 26, 2015. http://www.refworld.org/topic,50ffbce582,50ffbce5be,55929ef315,0,,,SVK.html.

I Furnas, Alexander. “Transparency Case Study: Public Procurement in the Slovak Republic.” Sunlight Foundation Blog. August 12, 2013. http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/.

II Furnas, Alexander. “In Slovakia, Government Contracts Are Published Online.” Sunlight Foundation. http://www.opengovguide.com/country-examples/in-slovakia-government-contracts-are-published-online/.

III To arrive at this number, a professional polling company was employed to undertake personal surveys with at least 1,000 people in 2012 (out of a country of 5 million) and their demographics were recorded (age, education and region). A follow up survey was undertaken early this year which showed that annual use is around 8 percent. GovLab interview with Gabriel Sipos, Director of Transparency International, August 4, 2015.

IV Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

V Sipos, Gabriel, Samuel Spac, and Martin Kollarik. “Not in Force Until Published Online: What the Radical Transparency Regime of Public Contracts Achieved in Slovakia.” Transparency International Slovakia. 2015. http://transparency.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Open-Contracts.pdf.

VI “Doing Business in Slovak Republic.” Doing Business–World Bank Group. 2015. Accessed July 14, 2015. http://www.doingbusiness.org/data/exploreeconomies/slovakia#dealing-with-construction-permits.

VII Kicina qtd. in Furnas, Alexander. “Transparency Case Study: Public Procurement in the Slovak Republic.” Sunlight Foundation Blog. August 12, 2013. http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2013/08/12/case-study-public-procurement-in-the-slovak-republic/.