The Global Impact of Open Data

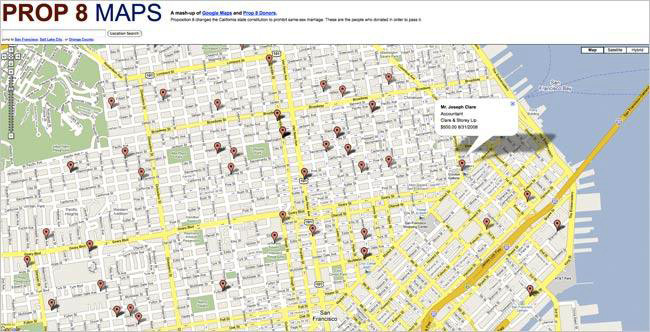

United States' Eightmaps

The unintended negative consequences of open data

by Auralice Graft, Stefaan Verhulst and Andrew Young*

Reference

1 Special thanks to Akash Kapur who provided crucial editorial support for this case study, and to the peer reviewers [odimpact.org/about] who provided input on a pre-published draft.

2 Alexander, Kim. “Initiative Disclosure Reform: Overview and Recommendations.” Greenlining Institute. June 16, 2011. http://www.calvoter.org/issues/disclosure/pub/greenliningpaper.pdf

4 Messner, Thomas M. “The Price of Prop 8.” Heritage Foundation. October 22, 2009. http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2009/10/the-price-of-prop-8

5 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

6 Alexander, Kim. “Initiative Disclosure Reform: Overview and Recommendations.” Greenlining Institute. June 16, 2011. http://www.calvoter.org/issues/disclosure/pub/greenliningpaper.pdf

7 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

8 Senate Bill No. 49, Chapter 866. http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/pub/97-98/bill/sen/sb_0001-0050/sb_49_bill_19971011_chaptered.pdf

9 Alexander, Kim. “Initiative Disclosure Reform: Overview and Recommendations.” Greenlining Institute. June 16, 2011. http://www.calvoter.org/issues/disclosure/pub/greenliningpaper.pdf

10 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

11 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

12 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

13 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

15 California General Election – Official Voter Information Guide. November 4, 2008. http://vigarchive.sos.ca.gov/2008/general/argu-rebut/argu-rebutt8.htm

16 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

17 “Proposition 8: Who gave in the gay marriage battle?” Los Angeles Times. http://projects.latimes.com/prop8/

19 Richardson, Valerie. “Pestered Prop 8 donors file suit.” The Washington Times. March 23, 2009. http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2009/mar/23/pestered-prop-8-donors-file-suit/?page=all; “Boycotts related to California Proposition 8.” BallotPedia. http://ballotpedia.org/Boycotts_related_to_California_Proposition_8

20 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

21 Roy, Jessica. “Gawker Slammed for Story Outing Condé Nast Exec.” New York Magazine. July 17, 2015. http://nymag.com/thecut/2015/07/gawker-slammed-for-story-outing-conde-nast-exec.html

22 Tate, Ryan. “Map of Anti-Gay Donors Created by Big Chicken.” Gawker. February 8, 2009. http://gawker.com/5149276/map-of-anti-gay-donors-created-by-big-chicken

24 Stone, Brad. “Prop 8 Donor Web Site Shows Disclosure Law Is 2-Edged Sword.” The New York Times. February 7, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/08/business/08stream.html?_r=0

25 “Google Map: Intimidation or Conversation Starter?” WND. February 11, 2009. http://www.wnd.com/2009/02/88616/

26 Stone, Brad. “Prop 8 Donor Web Site Shows Disclosure Law Is 2-Edged Sword.” The New York Times. February 7, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/08/business/08stream.html?_r=0

27 “Eightmaps.com and too much information.” The Dallas Morning News. January 14, 2009. http://dallasmorningviewsblog.dallasnews.com/2009/01/eightmapscom-an.html/

28 Keeling, Brock. “Map of Prop 8 Donors.” SFist. January 9, 2009. http://sfist.com/2009/01/09/mash-up_map_of_google_maps_and_prop.php

29 “Exposing bigots: eightmaps.com.” The Planetologist. February 14, 2009. https://planetologist.wordpress.com/2009/02/14/exposing-bigots-eightmapscom/

30 Lincoln, Ross A. “Eightmaps.com: Hypocritical Privacy Violation, or Reverse-Super Judo?” LAist. February 19, 2009. http://laist.com/2009/02/19/for_people_concerned_that_the.php

31 Tate, Ryan. “Map of Anti-Gay Donors Created by Big Chicken.” Gawker. February 8, 2009. http://gawker.com/5149276/map-of-anti-gay-donors-created-by-big-chicken

32 Stone, Brad. “Prop 8 Donor Web Site Shows Disclosure Law Is 2-Edged Sword.” The New York Times. February 7, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/08/business/08stream.html?_r=0

33 Richardson, Valerie. “Pestered Prop 8 donors file suit.” The Washington Times. March 23, 2009. http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2009/mar/23/pestered-prop-8-donors-file-suit/?page=all

34 “Google Map: Intimidation or Conversation Starter?” WND. February 11, 2009. http://www.wnd.com/2009/02/88616/

35 Richardson, Valerie. “Pestered Prop 8 donors file suit.” The Washington Times. March 23, 2009. http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2009/mar/23/pestered-prop-8-donors-file-suit/?page=all

36 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

37 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

38 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

39 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

40 “Prop 8 Donors: Find Out Who Backed California’s Anti-Gay Marriage Amendment.” The Huffington Post. May 25, 2011. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/02/02/prop-8-donors-find-out-wh_n_163234.html?ir=India&adsSiteOverride=in

41 Egelko, Bob. “Prop. 8 campaign can’t hide donors’ names.” SFGate. January 30, 2009. http://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Prop-8-campaign-can-t-hide-donors-names-3174252.php

42 GovLab interview with Daniel Kreiss, Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina School of Journalism and Media, September 18, 2015.

43 Stolz, Kim. “Are Prop 8 Opponents Using EightMaps.com for the Right Reasons?” MTV News. February 10, 2009. http://newsroom.mtv.com/2009/02/10/are-prop-8-opponents-using-eightmapscom-for-the-right-reasons/

44 Karger, Fred. “Fighting for Civil Rights Has Consequences.” The Huffington Post. November 21, 2009. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/fred-karger/fighting-for-civil-rights_b_294273.html?ir=India&adsSiteOverride=in

45 Wildermuth, John. “Mozilla’s Prop. 8 uproar reveals much about tech, gay rights.” SFGate. April 11, 2014. http://www.sfgate.com/politics/article/Mozilla-s-Prop-8-uproar-reveals-much-about-tech-5393875.php

46 Wildermuth, John. “Mozilla’s Prop. 8 uproar reveals much about tech, gay rights.” SFGate. April 11, 2014. http://www.sfgate.com/politics/article/Mozilla-s-Prop-8-uproar-reveals-much-about-tech-5393875.php

47 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

48 Johnson, Deborah G., Priscilla M. Regan and Kent Wayland. “Campaign Disclosure, Privacy and Transparency.” William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, Vol. 19, No. 4. 2011. http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1585&context=wmborj

49 Johnson, Deborah G., Priscilla M. Regan and Kent Wayland. “Campaign Disclosure, Privacy and Transparency.” William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal, Vol. 19, No. 4. 2011. http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1585&context=wmborj

50 Stone, Brad. “Prop 8 Donor Web Site Shows Disclosure Law Is 2-Edged Sword.” The New York Times. February 7, 2009. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/02/08/business/08stream.html?_r=0

51 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

52 GovLab interview with Daniel Kreiss, Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina School of Journalism and Media, September 18, 2015.

53 GovLab interview with Ira Rubinstein, Research Fellow and Adjunct Professor of Law at New York University, September 14, 2015.

54 GovLab interview with Ira Rubinstein, Research Fellow and Adjunct Professor of Law at New York University, September 14, 2015.

55 GovLab interview with Daniel Kreiss, Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina School of Journalism and Media, September 18, 2015.

56 Alexander, Kim. “Testimony at Public Hearing of the Fair Political Practices Commission’s Subcommittee on the Political Reform Act & Internet Political Activity.” March 17, 2010. http://www.calvoter.org/issues/disclosure/pub/031710KAremarks.html

57 GovLab interview with Kim Alexander, President and Founder of the California Voter Foundation, September 16, 2015.

58 GovLab interview with Daniel Kreiss, Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina School of Journalism and Media, September 18, 2015.

59 “Voter Privacy in the Digital Age: Recommendations.” California Voter Foundation. June 9, 2004. http://www.calvoter.org/issues/votprivacy/pub/voterprivacy/recommendations.html